Blood of the Lamb

Globe Theatre, 104 London St, Dunedin

20/09/2018 - 29/09/2018

Production Details

With wit, love, music and comic-tragic theatrical invention, Blood of the Lamb examines the life of a not-so-ordinary Kiwi family. As one of the founding figures of New Zealand theatre, Bruce Mason rewrote the rule book about what New Zealand theatre could say. Blood of the Lamb asks us to consider the spiritual and emotional cost of accepting ourselves and others for what we are, not what we want the world to see.

Dates

Thursday 20 September 7.30pm

Friday 21 September 7.30pm

Saturday 22 September 7.30pm

Sunday 23 September 2.00 pm

Tuesday 25 September 7.30pm

Wednesday 26 September 7.30pm

Thursday 27 September 7.30pm

Friday 28 September 7.30pm

Saturday 29 September 7.30pm

CAST

Henry- Helen Fearnley

Eliza- Toni White

Victoria- Anna Dawes

A Singer- Jessica Little

CREW

Taonga Puoro Composition and Performance – Jennifer Cattermole

Stage Manager – Alison Cowan

Costumes – Sofie Welvaert

Direction and Design – Richard Huber

Lighting and Sound Operator- Craig Storey

Lighting – Brian Byas and Craig Storey

Painting and Construction – Ray Fleury

Soundscapes and Editing - Craig Storey

Front of House Manager – Leanne Byas

Theatre ,

1 hour, 45 minutes

Bold directing of lyrical writing has powerful impact

Review by Terry MacTavish 22nd Sep 2018

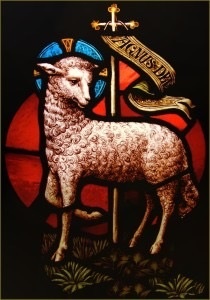

The brutal sacrifice of the Lamb, hung high on a tree, its blood dripping down on the violent destruction of innocence taking place beneath: that image, both literal and symbolic, has never lost its power for me since I saw the original production of Bruce Mason’s play in 1980. That audience gave it a standing ovation. Will Blood of the Lamb resonate as strongly with today’s more sophisticated audience, accustomed to gender-fluidity and unlikely to experience the nausea so frequently described in the script at the very idea of same-sex love?

Director Richard Huber has come up with an ingenious solution. Forget the meticulously realistic set that Mason details – we are ushered into a rearranged Globe Theatre with a traverse stage, bare but for a couple of seats, and just two rows of spectators on either side. It feels very like being on a jury, which can hardly be accidental. It means we are aware of the reaction of those on the other side – lights are on us for much of the time, and we are forced to take sides as the actors confront each other from opposite ends, allegiances changing as one character after another is isolated, combining for a final tableaux like a Victorian family portrait.

The classic play immediately seems more contemporary, our imaginations flesh out the scenes more convincingly than anything clumsily representational could do, and the intimate atmosphere generated is used to advantage by the actors. Despite Henry’s lively song-and-dance numbers, this is not a play that requires choreographed fight scenes and complicated stage business. Victoria is to be the judge, while her parents deliver their poignant backstory in a series of monologues that sit easily with such staging.

Another intriguing aspect to this production is the inclusion of an eighteenth century opera singer (beautifully bewigged and gowned thanks to costumier Sofie Welvaert). A construct of Henry’s imagination, the Singer materialises when he bursts into song. It is a pleasure to see Jessica Little back on the local stage in this role, a treat to enjoy her singing and sparkling, slightly mischievous presence.

Mason, who worked with Inia Te Wiata, liked to incorporate music, including in this instance the comically excruciating sounds of Henry learning the oboe. Huber has employed sound operator Craig Storey to introduce more than just the ravishing strains of Mozart, with a luscious pastoral soundscape naturally featuring the bleating of contented sheep. It is the music that really matters though, as the Higginsons are cultured in the extreme, and that culture is English, with seemingly every third line a literary or classical reference.

In New Zealand Theatre month, however, it is satisfying that the Globe has mounted a play that its author insists must not be transposed out of Aotearoa. Jennifer Cattermole is credited with the haunting sounds of Taonga Puoro that lend ritual and mystery to what might appear merely melodramatic. Mason’s commitment to Māoritanga means he has developed his theme of sexual exploitation to encompass colonisation and the rape of the land. “Screw. Kill. Erect. Male civilisation, and fuck it, if that’s the best it can do.”

Mason, commissioned to write for one twenty-ish and two forty-ish actresses, confesses to experimenting with some pretty ghastly ideas before he happened on this mostly true story. He had been reading Marilyn French’s seminal work, The Women’s Room, and like many men of my acquaintance then, had his eyes opened to sexual politics. For its time, Blood of the Lamb was a bold and well-intentioned effort. The characters still appear idiosyncratic and funny, with some wonderful evocative speeches, and a fascinating story to tell. The politics don’t seem to have changed all that much, either.

It is Māori of the East Coast who give refuge to the violated Gladys and Jennifer, her BFF of those innocent school and uni days, later her lover and partner. But when the situation is made clear, they too reject the girls, who then assume the identity of an orthodox married couple, called, in homage to G.B. Shaw, ‘Henry and Eliza Higginson’. Fortuitously, they inherit money and move south to grow flowers in Canterbury and bring up Henry’s daughter, Victoria. The play opens with the nervously anticipated visit of Victoria, who had run away without explanation when she was sixteen, and is returning after five years with her Italian-Australian fiancé. She may want them to give her a wedding. She will certainly want the truth.

We have to suspend disbelief, of course – Victoria may have been at boarding school, but that still leaves three months a year of holidays, and Henry’s disguise isn’t exactly convincing. Mason might have given more weight to yet another sacrifice of the lamb: to send away an adored six year old must be as appalling for the parents as for the child. Society may have cruelly prevented Henry and Eliza from being true to themselves, but the deception they consequently practise on their precious daughter is just as heartless.

Helen Fearnley is splendid as Henry Higginson, nee Gladys Mary Talbot, who is coerced into an engagement with a handsome brute who is determined to establish dominance over her. Fearnley brings a joyful exuberance to Henry’s wild cavortings, while allowing us to sense this near-manic behaviour is a cover for the strain of the revelation she must give and the judgement she must face. The climactic rape monologue is impeccably delivered, Henry’s histrionics and innate humour balanced by her quiet pain, deep-felt shame and anger, and always shining through, her resilient courage.

As Eliza, Toni White makes a comfortable, placid foil to flamboyant Henry. Her portrayal is very mumsy, and though it makes it hard to believe the girls were educated at the same exclusive boarding school, it validates Victoria’s affectionate description of her as a ‘sweetie’ as she sits sewing hundreds of seed-pearls to Victoria’s wedding veil.

Anna Dawes as Victoria is all her fond parents have claimed in beauty and elegance, although perhaps she could be more brittle and tense, given what is at stake. From the start her movements are relaxed and consciously graceful, although her vocal delivery favours speed over clarity. Fortunately this is less of a problem in the intimacy of the traverse.

Lest the ending seem too pat, Huber has extended a device employed throughout: the voices of the actors are recorded and played back with the scratchy sound of an old LP. The distancing effect of this helps us accept what would otherwise be an implausibly swift and tidy resolution, given the years of determined deception.

In his review of a 2006 production, John Smythe notes, “Achieving credibility is the play’s great challenge”. Paradoxically the abandonment of a realistic setting in Huber’s 2018 production makes it more believable, and junior members of the audience seem as swept up in the narrative as their seniors. The two wide-eyed young women in the row in front of me do not hesitate to use the word ‘shocking’. They are genuinely anxious to see how Victoria, with whom they identify, will react to the story at last revealed to her.

Thanks to Huber’s bold directorial decisions as well as to Mason’s lyrical writing, it seems the impact of Blood of the Lamb will linger in their memories, as it has in mine.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments