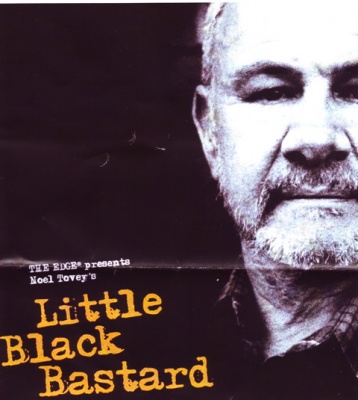

Little Black Bastard

Herald Theatre, Aotea Centre, The Edge, Auckland

02/05/2006 - 07/05/2006

Production Details

Written and performed by Noel Tovey

Directed by Robina Beard

Director, actor, playwright, novelist and choreographer Noel Tovey traces his fascinating heritage back to include the Plymouth Bretheren that settled in

Tovey escaped

In Little Black Bastard, Noel recalls his return to

Theatre , Solo ,

1hr 40 mins, no interval

From darkness he shines: highly polished

Review by Denis Edwards 03rd May 2006

This is the second of two Australian works now playing in Auckland. Both shine into an Australia that gives an answer to television’s demand, "Where the bloody hell are you?" On the basis of these works it is a clear, "If you have any sense it’s anywhere but there."

Louis Nowra’s The Jungle and now Noel Tovey’s Little Black Bastard offer the Sydney and Melbourne, respectively, of our worst imaginings.

Tovey’s story is pure Australian Gothic. His Melbourne is a bleak, hard place and his early life left little possibility of a middle ground. He would rise and soar or fall hard and brutally fast; dead in an alley, overdosed, shot or beaten to death, or dying alone in a cell.

While he had the apprenticeship for a lengthy career in crime he became something else. Tovey has enjoyed fame in London and around the world, as a dancer, actor and director.

This is a one-man play he has been taking around Australia, to acclaim and success. It is his story, beginning with a killer line, "The trams were my songlines." Unfortunately, after using the them to introduce his Melbourne, he parks the trams and leaves them. We do not particularly notice.

He covers a vast amount of material in his hundred minutes, perhaps a tad too much by zipping past moments when we might have revelled in a little more and for longer. For instance, lingering on what had to be some of the most gloriously clumsy ballet lessons ever would have given a moment’s pause in an often intense journey.

His story details the damage he suffered. The sexual exploitation that began long before he reached the age of ten was prolonged and occasionally violent, and the old saw that "damaged people are dangerous, for they know they can survive" runs under his story.

Tovey had the sense and the drive to take his few chances. It was first the military and then live theatre, Repertory as Redemption, that saved him, after his spectacular ancestry had him tightly pigeonholed in Australia as Aboriginal, opening him to the full blast of its 1940’s and 1950’s racism.

Nothing is being given away here. The publicity and programme material say this much.

As a performer Tovey keeps it simple, working in a plain and well-designed set. He is in black, with an unobtrusive lighting plan supporting the dark themes. For a few moments the lighting, during a scene in prison, almost tells its own story.

Given he is no longer burdened with youth, Tovey keeps clear of anything too physical, although glimpses of his dance background – a moment of arm work at the bar and a couple of tap steps – give us a quick look at a reservoir of skill and talent we suspect could be their own show.

Not one to let us off with jokes, Tovey goes instead for a nicely worked irony; his worst abuser unknowingly supplies the famous relative Tovey needs to begin the journey out of an appalling existence. And being a little black bastard turns out to work extremely well for him, when official documentation offers him another opportunity at escape. It is possible to ask how he got away with a new identity, after his face and name were splashed through the Melbourne newspapers in a high profile trial. But, this is a minor quibble.

His voice, polished with elocution lessons which would get him beaten up, carries the play for him. It is the accent Clive James, Rolf Harris and Barry Humphries learned, either on or before getting the boat for London, pitched somewhere between BBC English and Australian. Scoffed at as part of the ‘cringe’, it served them well, carrying them to heights their scoffers seldom reached.

With hundreds of performances safely behind him Tovey has the material thoroughly sanded down and while he never quite relaxes – he is reliving some brutal moments – his voice holds us. For a local working actor this is a useful master class in diction, and the power of tone.

Little Black Bastard is a strong, rich piece. The voice is not one that lands here often, which makes it a play that rewards us for listening as much as for watching.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments