BACKSTAGE PASS Stories from Thirty Years of the Auckland Theatre Company

A bookshop near you/buy online, (not a specified venue)

01/01/2024 - 31/12/2024

Production Details

By Frances Walsh

Published by Penguin Random House New Zealand, 2023

A lively and entertaining look at the Auckland Theatre Company – its people, its shows, the backstage crew, the theatre, and the company’s ups and downs over the years.

Auckland Theatre Company has presented a huge range of plays to enthusiastic audiences since its first show in 1993 – Lovelock’s Dream Run. From Shakespeare and Chekhov to Nathan Joe and Oscar Kightley, variety has been key with a strong Kiwi sensibility throughout.

Rising from the ashes of the Mercury Theatre after its abrupt closure in 1992, the fledgling company struggled to find venues and moved around the city using spaces as they found them, until setting up home in the fabulous purpose-built ASB Waterfront Theatre.

The many personalities, shifting fashions and cultural expectations, artistic disagreements, talented contributors and wildly successful shows through changing times lead to a colourful patchwork of stories that make a thoroughly enjoyable read.

About the author

Frances Walsh is an award-winning journalist and writer. Her 2020 book Endless Sea: Stories Told Through the Taonga of the New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui te Ananui a Tangaroa was long-listed in the Ockham NZ Book Awards. She has also worked as the organiser for Equity New Zealand, the trade union for performers.

Buy from…

The Nile | Mighty Ape | BookHub Whitcoulls |

The Warehouse | Paper Plus | Fishpond

View all retailers Find local retailers

Published: 14 November 2023

ISBN: 9781927158418

Imprint: Penguin

Format: Paperback

Pages: 336

RRP: $50.00

Categories:

Local interest, family history & nostalgia

Theatre studies

Theatre , Book ,

Richly resonant and revealing

Review by John Smythe 10th Apr 2024

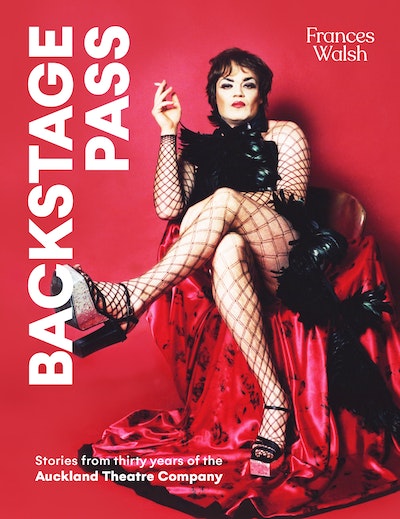

Subtitled ‘Stories from Thirty Years of the Auckland Theatre Company’, the bright red BACKSTAGE PASS cover features Joel Tobeck glammed up as Frank’N’Furter. It’s a marketing still (by John McDermott) for ATC’s production of The Rocky Horror show by English/Kiwi writer-performer Richard O’Brien. A double-page spread mid book and the invaluable List of Productions in the Appendix reveals it played Auckland’s Sky City Theatre in 2002 and Wellington’s St James in 2003. It would be pointless to debate whether the cover image represents the essence of the company’s kaupapa because that is ever-evolving, as it should be. The point is, it’s eye-catching and provocative.

Award-winning journalist and writer Frances Walsh (whose CV includes being an organiser for Equity New Zealand) has risen with alacrity to ATC’s challenge to “tell the company’s rich history succinctly” in a way that is “interesting to those inside the story and to the general reader”. Her extensive Introduction contextualises the company’s dramatic origin story then summarises the whole 30 years (1993-2023) in lively text, vividly supported – as is the entire book – by evocative production photos which tell their own stories and are mostly tagged with names of the pictured actors, the production’s title and year, plus a photographer credit.

Puzzling exceptions include the failure to name Madeleine Sami, Lucy Lawless and Danielle Cormack in a triple publicity image for The Vagina Monologues, 2002 (p61), and the Kit Kat Boys and Girls from Cabaret, 1999 (pp84-85). That double page spread, which carries a quote from PM-elect Helen Clark, also suffers from bad spine alignment. Otherwise naming the shows and year of production allows useful cross-referencing with the full credits in the Appendix.

The absence of an Index, however, severely reduces the book’s searchability – a bewildering omission, not least because the first thing anyone who has worked with the ATC would look for, on wondering whether to buy it, would be their name in the Index. More importantly, the lack of an index decreases the book’s value to anyone researching any aspect of performing arts practice in Aotearoa NZ.

The Introduction sets the scene with dramatic conflicts that capture the nature of theatrical enterprise:

‘MS and DM beg to differ’, shares letters from two audience members with opposing opinions of the 1999 production of Patrick Marber’s Closer;

‘The Disruptor’, lists the countless shows in various stages of development or production that were interrupted or cancelled thanks to Covid-19 restrictions and lockdowns;

‘Ducking and diving during Covid-19’, details the many and varied creative initiatives ATC launched to keep their communities of interest connected – and concludes with the winning entry in the 100(ish) Wordplays Project and Competition.

I find myself delighted at discovering things I hadn’t known about, and briefly perturbed that Eleanor Bishop and Eli Kent’s brilliant online adaptation of Chekhov’s The Seagull in response to Lockdown 2020 only seems to get a cursory mention – until I check the Contents again and realise there’s a chapter entitled ‘Chekhov in the time of a pandemic: Eleanor Bishop and Eli Kent’.

Dipping in and out of chapters that take your fancy is clearly an option but the not-always chronological order in which people are centred in chapters through interviews and research, or ‘in their own words’, does embody the evolution of values and priorities as time moves on.

‘The Instigator: Simon Prast’ covers his experience of being evicted from a pulsating but broke Mercury Theatre, being anointed as ‘heir apparent’ by the company’s now ex-artistic director Raymond Hawthorn, aligning corporates, philanthropists and the ‘industry’ to a new vision, taking risks and playing safe to keep this new baby alive … ‘An encounter with darkness’ allows designer Tony Rabbit to share a rather gruesome anecdote about a Daughters of Heaven prop. Prast’s ill-judged attempt to censor critics gets a couple of pages, headed ‘The Robert Mugabe of New Zealand theatre’.

Quite why Walsh, in her intro to ‘On track: David Geary’, chooses to accuse Prast of “flag-waving like a jingoist” because he expressed pride that the ATC is launching itself with Lovelock’s Dream Run, about, by and produced by New Zealanders, escapes me. Such barbs pepper the book in what feels to me like an unnecessary attempt to prove the writer is not just writing a panegyric. This section traces: the creation of the play by Geary, which draws heavily on his experience of boarding school; Damon Andrews’ experience (as Howard) of working with Bruce Hopkins (Pike); a segue between Lovelock and Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa involving actor Robert Pollock and ‘A triggering three piece suit’ which is odd but interesting.

Geary gets more attention in ‘Down country’, profiling his commitment to “putting the country on stage” (meaning rural NZ) and creating “big physical challenges” with The Learner’s Stand (1995) about shearing, which includes a transgender rousie, Dawn (played by Georgina Beyer). Walsh pops a sting in the tail of that tale, too.

‘She’s hot: The summer of ’98’ profiles the rise and fall of ATC’s ‘Seven Plays of Passion’ season subverted by a Mercury Energy infrastructure failure that inflicted a five-week power outage on Auckland’s CBD, afflicting The Herbal Bed’s truncated season at The Maidment. The programme note from its sponsor Kensington Swan gives readers an idea of what they might have missed. And five quotes from rave reviews of 12 Angry Men mark Simon Prast’s directorial debut.

While seeming to go off topic, Paul Minifie’s summary of the first 30 years of his experiences in theatre, before he became director of the University of Auckland’s Maidment Theatre, does give a useful overview of professional theatre activity in the North Island. Unfortunately no-one picked up the error, “Downstage opened in the 1970s” (p86). That was The Hannah Playhouse; Downstage Theatre had been going since 1964 before it was housed in that purpose-built space. Minifie’s commitment to elevating the Maidment from ‘school hall’ to a well-run theatre saw the venue become ATC’s ad-hoc home (they had been performing at The Watershed and Sky City Theatre). His entertaining recollections and anecdotes cover 18-years, from Prast at the helm to Colin McColl becoming Artistic Director, and includes the demolishing of the Maidment and ATC’s commissioning of the ASB Waterfront Theatre.

‘Mr Rock’n’roll: Oliver Driver’ covers his tenure (2000-2004) as the 20-something Associate Director to Prast, heralding a push for new blood on stage and in the audiences. It touches on his directorial debut with David Hare’s The Blue Room starring Danielle Cormack and Kevin Smith, and his problems with reviews – even more so when a critic took him to task for cutting a scene from Neil LaBute’s The Shape of Things.

The success of ATC’s 10th anniversary season (2002), which climaxed with the box-office hit of Richard O’Brien’s The Rocky Horror Show directed by Prast, is contrasted with the risk he took in 2007 with The Pillowman (by Martin McDonagh). Driver, now freelancing and in the cast, tells of observing interval walk-outs. Production images of that and of Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (directed by Colin McColl in 2001) both feature Driver and Craig Parker.

Walsh marks the selection of the highly experienced Colin McColl to succeed Prast as artistic director, in 2003, by quoting Driver’s view that “seventeen boring years” followed; that three similar white men have run the ATC over its 30 years: “when are we going to get Katie Wolfe in charge? When are we going to get somebody else who has a completely different view of the world?” Yet Driver does concede ATC is “currently good theatre … It’s easy to sit on the sidelines and pick holes in it … it’s much harder when you’re the one doing it.”

The story of Kristian Lavercombe’s Jesus Christbeing accidentally stoned, by gifted cookies, on the opening night of Jesus Christ Superstar (directed by Driver, 2014), gets a lively telling as ‘The best drug story’. Danielle Cormack is the common denominator in ‘Gender politics’. It tells us how moral outrage ensured full houses for Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues (Driver, 2002). In noting the different approaches in the ATC (Driver) and Circa Theatre (Wellington; McColl) productions of The Blue Room – David Hare’s adaptation of Arthur Schintzler’s controversial La Ronde – directed respectively by Driver and McColl, an outrageous aspersion on the acting abilities Cormack and her co-star Kevin Smith is ascribed to McColl by a Wellington reporter. The brief account of Tennessee William’s A Streetcar Named Desire offers Cormack’s perspective on questionable decisions by the director (Prast) and designer (Tracy Grant Lord). A reference to the later section about intimacy co-ordination might have been appropriate here.

Profiling John Verryt’s (non-exclusive) 30 year relationship with ATC wraps his personal progression from graphic designer through stage manager to set designer in an interesting overview. I’m disappointed, however, to see ‘the fourth wall’ described (by Walsh, who may or may not be paraphrasing Verryt) as “that imaginary wall that keeps performers and audiences distanced from each other and from the play itself.” This ignores the reality and value of empathetic connections that can draw audiences into the hearts and minds of human experiences being shared in naturalistic plays.

The chapter on Roger Hall’s contributions to the ATC’s coffers, entitled ‘The catnip’, begins with another error by naming his first play Gliding On. That was the TV series spinoff from Glide Time (which premiered at Circa in 1976). The 16 Hall plays (of the 40 he’s written) that ATC produced tended to be his most recent, from By Degrees in 1994, cited by Hall as proof men can write credible female characters, to Winding Up in 2020. The exception is Middle Age Spread (written in 1997) which is comprehensively discussed. So are Four Flat Whites in Italy (2009), Who Wants to be 100? (2007) and Social Climbers (1977) with photos illustrating all of them – including the shot of a bedraggled, mascara-running Jennifer Ludlam in the latter, to which Hall objected.

Hall is otherwise complimentary about the ATC productions of his plays – plus he gets to pick five of his favourites by other playwrights, of which four are homegrown.

Although Colin McColl’s tenure as Artistic Director lasted 18 years, Walsh calls him ‘The Two-Decade Man’. He’d directed nine ATC productions in the freelancing decade prior to 2023 yet his welcome as AD was “less than effusive”. His experience and value were soon appreciated, however. The ten pages that sum up the McColl years vividly track the eclectic range of mainstream productions and the essential moves towards cultural inclusivity and collaboration, balancing new and classical NZ plays with refreshing and often controversial revisions of classics, like Ibsens’ Peer Gynt [Recycled] by Eli Kent (2017) and Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard (2018) adapted by McColl, Albert Belz, Philippa Campbell and Tainui Tūkiwaho, who relocate it in 1970s Hawkes Bay.

Following mentions of the highly successful productions of Bruce Mason’s The Pohutukawa Tree (2009) and Awatea (2012), directed by McColl, and an ensemble version of The End of the Golden Weather (2011, directed by Murray Lynch), I’m perturbed to read: “These days, says McColl, you could question whether Mason’s plays should be staged at all: ‘It’s kind of a white man’s view of this world.’” Well, yes – and? Mason’s plays on Māori themes insightfully critique the ‘white man’s’ impact on te ao Māori and his ‘loss of innocence’ play wrestles with what it means to be a ‘man’ in NZ – themes that remain very relevant today. That’s what makes them classics, able to speak to every generation.

Community outreach and youth programmes run by Second Unit Co-ordinator Lynne Cardy – who gets her own chapter later in the book – get their due along with ATC’s mainstream collaborations with the Pacific Institute of Performing Arts (PIPA), Te Rehia Theatre, Prayas Theatre and Proudly Asian Theatre, all ensuring a comprehensive range of Auckland citizens are represented in the region’s leading subsidised theatre. Not only did McColl direct 54 productions during his tenure (making his ATC total 63), he and General Manager Lester McGrath also worked with Moller Architects to find the site and create the permanent home that would become the ASB Waterfront Theatre – an enterprise that also gets its own chapter.

Gordon Moller also talks ‘On demographics’, characterising ATC’s core audience as “eastern suburbs” by way of explaining what worked and didn’t. There are sections encapsulating pro and con reviews and audience feedback on McColl’s treatments of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya (1996) and the aforementioned The Cherry Orchard (2018).

A rich array of diverse and insightful personal, collegial and socio-political perspectives follow:

‘Channelling George Henare’ covers the actor’s ATC track-record over 20-odd years. Prast interviews Raymond Hawthorn on how he interpreted Julius Caesar (1998). Writer/actor Nicola Kawana recounts key experiences in her own words, exquisitely written. Costumiers Elizabeth Whiting and Stephen Junil Park respond to design briefs.

Actor/ writer/ director Goretti Chadwick encounters racism post-PIPA then grows her skills at ATC, culminating with D.F. Mamea’s made for touring Still Life with Chickens (2018+). Writer/ producer Victor Rodger critiques ATC as “Almost Totally Caucasian” before he got to put Pasifika centre stage with his “provocative adult play” My Name is Gary Cooper (2007), and comments on what’s happened since.

Educator Lyne Cardy’s seventeen year term is “the driving force behind the company’s youth, education and community programmes includes mentions of Shrew’d (2008) devised with director Margaret-Mary Hollins, Jo Randerson’s Cow, Gary Henderson’s Tiger Play and Tom Sainsbury’s Disorder (2011), Eleanor Bishop’s adaptation of Greg McGee’s Foreskin’s Lament, Boys (2017). She cites Michael Hurst’s adaptation of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata (2015) as an example of how she and chorographer Shona McCullagh worked with teachers to create a programme for students.

Creative/performing artist and playwright Leki Jackson-Bourke writes positively of his twelve-year relationship with ATC, facilitated by Cardy, from performing in its PIPA collaboration Polly Hood in Mumuland (2011, by Lauren Jackson, directed by Goretti Chadwick) to premiering Inky Pinky Ponky (Next Big Thing 2015, co-written with Amanaki Prescott-Faletau and directed by Fasitua Amosa) then his ATC-commissioned The Gangster’s Paradise (2019 Here & Now Festival, directed by Amosa).

From playing The Player in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (2002) and Riff-Raff in The Rocky Horror Show (2003) to co-directing (with Benjamin Henson) and played the title role Shakespeare’s King Lear in 2023, actor/ director Michael Hurst performed in fourteen ATC shows and directed six. Walsh notes his responses to a number of topics, including his commitment to rigour and physicality.

Actor/ director/ president of Equity NZ Jennifer Te Atamira Ward-Lealand, who has acted in 29 ATC productions (including workshops) and directed two, illuminates the intricate art of intimacy co-ordination. This leads to accounts of August: Osage County (2010), ‘A charmed production’ – with snippets from sound designer/composer Eden Mulholland and lighting designer Phillip Dexter.

‘Acts of Resistance’ is the subtitle for the section that explores the evolution of creator/director Katie Wolfe’s superb verbatim play The Haka Party Incident. The subtitle could also apply to the ‘flashpoint’ that made Chye-Ling Huang challenge ATC’s lack of mainstage diversity.

‘In the Time of a Pandemic’ Eleanor Bishop and Eli Kent’s meet the challenge with a new online version of Chekhov’s The Seagull Act One, Act Two, Act Three, Act Four. This account of how the Zoom production evolved and was experienced offers a priceless example of how truly creative people can capitalise on adversity. An anecdote follows about designer Tony Rabbit’s design for McColl’s 1994 production at the Herald theatre. Strangely there is no mention of McColl’s Onstage/Onscreen lockdown production of Ibsen’s The Master Builder (2020).

Theatre maker Nathan Joe, whose Scenes from a Yellow Peril, directed by Jane Yonge, premiered in 2022, explains his progression from self-doubt to achieving a co-production with ATC, Oriental Maidens and SquareSums&Co, which also happened for Ankita Singh’s Basmati Bitch (2023, directed by Ahi Karunaharan). Joe’s enquiry into the status quo and his self-examination as a maturing practitioner is a lively read.

The 2022 ATC/Pacific Underground revival of Oscar Kightley’s Dawn Raids (written in 1997) also reinforces the value of well-resourced theatre companies actively seeking collaboration with other groups to meet their mandate to represent all cultures. In this case its relevance links to the long-awaited government apology. The section includes a poem from the Reverend Mua Strickson-Pua that captures is own experience of the dawn raids, and a playwright’s not from Kightley.

Sherry Zhang 章雪莉 (then Kaiwāwahi/ Editor of the Pantograph Punch), whose play Yang/Young/杨 (co-written with Nuanzhi Zheng) premiered at The Basement in ATC’s 2021 Here & Now Festival, directed by Nathan Joe, writes of the privilege of being able to speak freely compared with her playwright/theatre director grandfather and dancer grandmother’s experience during China’s Cultural Revolution. Not that her parents saw creative pursuits as a career path. Her turmoil around what she feels – “I do not carry the burden of representation for ‘Young! Emerging! Queer! Chinese! Writer!’ – and what she wants is personally revelatory yet highly relatable to anyone involved in the arts.

Appointed CEO of ATC in 2019, Jonathan Bielski also became the Artistic Director, under a fixed five year contract, when the positions were merged in 2021. Not that he’ll be directing any plays. Walsh devotes 10 pages, including images, to writing him up as ‘The Navigator’. His answers to her questions may be seen as evasive, defensive of provocative – e.g. re refuses to articulate his ‘vision’, which he sees as an overused, abused and therefore meaningless word in the arts sector. He’s reported as saying, or thinking, “We’re going to, ah, put on plays.”

Having admitted to being “a cisgendered man, middle-class, privileged and white,” Bielski sees his role as being “to lead the company into a ‘systematic, deep revision of how we do things’ without leaving anyone behind in the process.” He has enthusiastically embraced the collab model established by McColl, allowing ATC’s resources to empower other to work at scale. Given their privileged position, thanks to relatively secure funding via the Auckland Council’s Regional Amenities Act and a six-year contract with Creative NZ, Bielski carefully articulates the responsibilities inherent in managing an eight-million dollar turnover in the post-Covid environment.

Apparently he is still thinking about how go about commissioning and developing new works, now that Colin McColl, literary manager Philippa Campbell and Lynne Cardy have left the building. “When he departs,” writes Walsh, “he’s like to be able to say that during his time ATC welcomed, respected and valued anyone with talent … New audiences were connected in ways they never had before. Of paramount importance was that ATC and its storytelling reflected Tāmaki Makaurau.”

‘The last word’ comes from the Chair of the ATC Board of Directors, Vivien Sutherland Bridgwater (Ngāti Whātua). She mihis to Tāmaki Makaurau as “the land desired by many” and to all those who made the ATC what it has become over the last 30 years. “Over the past three years we have been reminded deeply of the need for human connection, and that is the taonga (treasure) that live theatre gives us.” Tautoko to that!

Overall Backstage Pass embodies particularities that will resonate with theatre practitioners and reveal intriguing details to theatre goers.

Errata

P33: Stephen Lovatt misspelt as Steven

(but correct in the Appendix production credits)

P86: Paul Minifie in his own words: “Downstage opened in the 1970s” – that was The Hannah Playhouse; Downstage launched in 1964.

Pp96 & 174: Shane Bosher misspelt as Boscher

(but correct in his Director credit for Long Day’s Journey Into Night (2022).

P114 “since 1976, when his first play, Gliding On, was performed, Roger Hall …” – the play that premiered at Circa (Wellington) in 1976 was Glide Time; Gliding On was the title of the TV sit-com series spinoff that premiered in 1981.

P164: Robin Payne misspelt as Robyn.

P204: The credits for a photo of the cast of Lysistrata (2015) dancing across a traverse stage mistakenly names Peter Hayden as Peter Daube and misspells Darien Takle as ‘Tackle’.

[Doubtless I have made errors too – if so, please let me know. – JS]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments