DEATH OF A SALESMAN

13/10/2012 - 27/10/2012

Production Details

DEATH OF A SALESMAN ‘STILL PACKS A PUNCH’

Following sold-out seasons world-wide, “America’s greatest play” DEATH OF A SALESMAN plays a limited season at Auckland’s Maidment Theatre from October 11th.

From its stunning run on Broadway, where it broke box office records, through to an extended run at Sydney’s Belvoir Theatre, Death of a Salesman has become a cultural phenomenon in terms of theatre show revivals – and Auckland now has a chance to understand the spirit of the world it once again captures with this strictly limited season.

Detailing the life of businessman Willy Loman and his son Biff, the pair have aspirations and dreams – one to work closer to home, the other to fulfil the potential he once showed. The downfall of the Loman family and the pressures of living up to other people’s expectations are motifs that have made Arthur Miller’s seminal masterpiece a work that resonates with today’s society more than ever.

The parallels of the struggles Miller penned in 1949 are eerily similar to those we face today in 2012. Economic downturn, struggles to make ends meet, ambitions quashed by realities – problems that upon the work’s debut occurred post-World War II, and problems that we’re facing ourselves post-“War on Terrorism.”

Such has been the works modern resonance that upon its revival, Death of a Salesman becomes one of the most critically acclaimed productions on Broadway this year. Starring Academy Award winner Phillip Seymour Hoffman in the role as Willy, the production earned numerous five-star reviews, 3 major 2012 Drama Desk Awards (including “Outstanding Revival of a Play”) and a hallowed Tony Awards for Best Revival of a Play – to name a mere few.

Peach Theatre Company understands the prestige of this production so has once again brought together in an incredible array of acting talent for this strictly limited season. Cast in the lead roles are George Henare OBE, Catherine Wilkin, Ian Hughes and Richard Knowles as the Loman family, while Ken Blackburn ONZM, Bruce Phillips, Anna Jullienne, Nic Sampson and Annie Whittle star alongside them for what will truly be a stunning New Zealand production of this incredible worldwide success.

“STILL VIBRANT. STILL POWERFUL.”– ASSOCIATED PRESS

Death of a Salesman plays:

11th – 27th October 2012

Maidment Theatre, 8 Alfred Street, CBD

Tuesday and Wednesday: 6:30pm.

Thursday to Saturday: 8pm. Sunday: 4pm

Matinee performance: Saturday October 27th 2012: 2pm

Preview Nights: 11th and 12th October: 8pm

Tickets: $30 – $57 (plus applicable booking fees)

TWENTY DOLLAR TUESDAY: October 16th – $20 (plus applicable booking fees)

Bookings through Maidment Theatre ph: 09 308 2383

or www.maidment.auckland.ac.nz

CAST

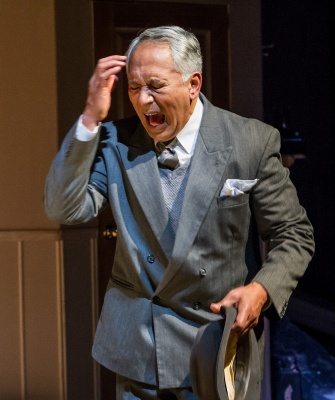

Willy Loman – GEORGE HENARE

Linda – CATHERINE WILKIN

Biff – IAN HUGHES

Happy – RICHARD KNOWLES

Uncle Ben / STANLEY – KEN BLACKBURN

The Woman – ANNIE WHITTLE

Charley – BRUCE PHILLIPS

Bernard – NIC SAMPSON

Howard Wagner – DWAYNE CAMERON

Miss Forsythe / Jenny – ANNA JULLIENNE

Letta – AIMEE GESTRO

Designer – EMILY O'HARA

Lighting Designer – RACHEL MARLOW

Costume Designer – LYNN COTTINGHAM

Music by ANTHONY YOUNG

Stage Manager – GREG PADOA

Technical Operator – KYLE PHARO

I’m sold

Review by Matt Baker 15th Oct 2012

In his opening night speech, director Jesse Peach obscurely alluded to the possibility of Death of a Salesman being his last production*. While I actively concede that this may have been a misinterpretation of inarticulate speech, I would like to think that going out on a high note is the correct course of action in the case of Peach Theatre Company, as a high note has now been achieved.

Programme notes and post-show audience commentary of the play beat the more-relevant-now-than-ever drum, yet, I would riposte, when has it not been? Even before we left the jungle, when have the concepts of success, monetary gain, parental delusion, parental worship, delusions of grandeur, self-achieved submission, and family not been relevant? A play’s success comes from the universality and timelessness of its themes, and, while the social, economic, and political climate of a city/country in which a play is produced should have some relevance, I found far more in the story between father and son than in that of the American Dream. This is not due to any lack on the part of George Henare as the eponymous salesman (there is, quite simply, nothing that Henare lacks as an actor) or the apathy-inducing over-abundance of economic/financial hardship we see purported in the media, but can instead be ascribed to the complexity, empathy, and power of Ian Hughes’ portrayal of Biff. [More]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Classic reading of Miller a Peach

Review by Paul Simei-Barton 15th Oct 2012

Peach Theatre’s reverential approach to Arthur Miller’s 1949 classic offers a traditional reading that allows this 20th century masterpiece to speak for itself – with all its ambiguities and contradictions intact.

In opting for a post-war setting, the production demonstrates there is no need for any up-to-the-minute modernisation to highlight the play’s continuing relevance.

The play speaks to contemporary audiences with an unsettling power due to Arthur Miller’s invigorating refusal to settle for easy answers and his profound respect for the struggles of ordinary people. [More]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tragedy in commerce more relevant than ever

Review by Nik Smythe 14th Oct 2012

In 1949, when all the post-war promises of the American Dream were still steadily on the rise, Arthur Miller saw an elephant in the room and wrote Death of a Salesman. In a world of opportunity there for the taking for anyone determined and ruthless enough, what of the casualties who were simply too sensitive and human?

The narrative ultimately lays bare the uneasy fact that the ideological American Dream is built on a scaffold of lies which, when exposed are apt to bring the whole infrastructure tumbling down. The insidiousness is such that the most humane way to protect the innocent is to perpetuate the delusion upon which their sense of self-worth is based.

George Henare, the reigning patriarch of classic Auckland theatre, delivers a heartbreaking portrayal of washed-up travelling sales-rep Willy Loman. Exhausted and frustrated, in his case the biggest lie is the one he tells himself: that loyalty and personality offer some kind of assurance for a secure future, when really the only thing that provides such assurance is the financial return his labours provide.

Catherine Wilkin is credible and endearing as loving wife and mother Linda, dutiful and long-suffering rock to her husband and sons. A seemingly bottomless source of genuine empathy and positive, forward thinking, she is the least deceitful and most deceived character in the story.

If Willy’s a has-been, his eldest son Biff is a never-was; though in his mid-thirties, the torment of estranged youth is apparent in Ian Hughes’ earnest performance. At one time a promising athlete, Biff strives to take all his father’s incongruous life lessons and adapt them into a practical philosophy that satisfies him and, ideally, doesn’t disappoint his parents too much.

Rounding off the small brood is Biff’s taller, better looking younger brother Harold ‘Happy’ Loman, played Richard Knowles with exemplary charm and swagger. Following in his father’s footsteps, Hap’s success may in part be due to the repeated spiritual affirmation proffered by his nickname. More likely it’s his willingness and understanding of how to play the game and tell the right lies, thereby avoiding the hot-seat that Biff is continually thrown into. A lack of concern for moral issues also helps.

The maddening complexity of Willy’s unravelling state of mind teems with unresolvable dilemmas, such as the love he clearly has for his oldest son, versus his disappointment with Biff’s lack of career success, versus repressed guilt for his own part in Biff’s underachievement. The drama is essentially natural in tone, yet the way Willy repeatedly contradicts himself echoes the absurdity of Pinter or Beckett and, with his advancing dementia, any capacity he may have held to reconcile these anxieties is severely dwindling.

The supporting cast is as well appointed as the central family, particularly Bruce Phillips’ entertainingly callous Charley, the Lomans’ next-door neighbour. His own career seems to be a cutthroat success story, but he has a soft enough spot for the people close to him to be there when they need help.

Nic Sampson draws some mirth as Charley’s nerdish son Bernard, particularly in flashback scenes where his uptight, studious demeanour is in direct contrast to the Loman boys’ idle jocularity (each reflecting their fathers’ own attitudes).

Lettered stage veteran Ken Blackburn MNZM’s Uncle Ben is perhaps the lynchpin of Willy’s torturous plight. The most financially successful of them all, he lacks Charley’s sense of humour and compassion for others less fortunate, including his own brother and family for whom he expresses little more than disdain back when he bothered to visit them at all. Nevertheless it’s Ben’s perceived advice that plays on Willy’s stubborn pride, as communicated via senile hallucination, which he ultimately takes to its woeful conclusion.

Blackburn’s age seems incongruous with his role given that his presence is only in Willy’s recollection of younger years, as does Annie Whittle’s in her spirited turn as the haunting memory of a carefree-but-significant indiscretion from his past. It’s hardly a distracting point however, thanks to the calibre of their talents.

Representing the status quo of modern commerce, Dwayne Cameron’s Howard Wagner cuts a ruthlessly disingenuous portrait of corporate cruelty as Willy’s young employer Howard, the son of the man who hired him. Meanwhile, in a typically pre-sixties bid to balance out the female component, Anna Julianne and Aimee Gestro provide impressive eye-candy as a couple of fine strumpets, game for a good time with a couple of notable lads. as Happy’s lies make him and Biff out to be.

The pervading pre-recorded original score composed by Anthony Young takes an almost cinematic approach; accentuating moments of poignancy both hopeful and devastating with flute-led soap-opera-like stings, then plunging into squalling strings-driven turbulence as the suffering of our protagonist demands.

Lynn Cottingham’s costume design is predominately an accurate snapshot of the cuts and sombre-toned hues of the age, with added colour and brightness from the young women’s frocks and Uncle Ben’s status-trumpeting white suit.

By contrast, Emily O’Hara’s visionary set design adds dimensional layers, with its wholesomely domestic tone and the ensuing transformation, mirroring the deterioration of Willy’s mind. The increasingly scuffed and scattered dirt on the ground symbolises fertility and death, in both real terms and the context of personal ambition.

Lighting designer Rachel Marlow has also spanned the realms of reality and hallucinatory vision most effectively. I particularly enjoy the occasional grotesque shadowplay that occurs incidentally across the walls, like manifestations of the characters’ (not just Willy’s) subconscious demons.

Jesse Peach’s accomplished direction drives the action with enough energy to keep some sense of momentum throughout two-and-a-half hours of circular arguments, sidetracks and second-guesses. Although the work is demonstrably solid, on opening night there were moments of stiltedness that gave the feeling the company was not quite running at full power. One or two of their variant American accents seemed to falter as well, causing momentary separation from the otherwise gripping drama.

Another wee side-criticism: the programme bangs on somewhat unnecessarily in a pseudo-tabloid fashion about Arthur Miller’s private life with Marilyn Monroe, which is undoubtedly popular gossip but bears no relationship to any other aspect of this production. Both more scandalous and more relevant is the expose article on his ostracised youngest son; mysteriously extreme treatment from such a renowned humanist as Miller, the reason for which he took to his grave.

Since Death of a Salesman premiered on Broadway, the American Dream has spread throughout the western world and beyond. Human beings are more disposable than ever in the eyes of the capitalist workforce, and more trapped in the domestic vicious cycles of student loans, mortgages and credit-card debt.

It’s risking cliché to suggest this generation-old play is more relevant than ever, but the horrific truth is that people can still be worth more dead than alive. Meanwhile, if Biff only took his deep-seated inadequacy far less seriously he could be a poster-boy for Generation X.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

nik smythe October 15th, 2012

It did mention he was down-syndrome, and although it was 'the done thing' it still seems uncharacteristc the way he didn't just send him away, he effectively erased every record he could of Daniel's existence. To Miller's credit, against legal advice, he wrote his estranged son into his will as a full and direct heir, only weeks before he died.

To be fait regarding the other article, it did in fact outline his career highlights and all three of his marriages. The impression of unnecessary emphasis I got was from the three accompanying photos, all of him and Marylin.

Phil Braithwaite October 15th, 2012

Good review, but just on that comment, 'Both more scandalous and more relevant is the expose article on his ostracised youngest son, mysteriously extreme treatment from such a renowned humanist as Miller, the reason for which he took to his grave.' I don't know what the article said, but there's nothing mysterious about what happened there - his son (Daniel) has down's syndrome and was locked away in an institution, which was the done thing back then. Read the second volume of Christopher Bigsby's biography, which has a chapter called 'Daniel' that explains it.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments