King Lear

ASB Theatre, Aotea Centre, Auckland

18/08/2007 - 25/08/2007

11/08/2007 - 13/08/2007

Production Details

by William Shakespeare

directed by Trevor Nunn

Composer Steven Edis

Lighting designer Neil Austin

Designer, set design and costumes Christopher Oram’s

Fight design and choreographer Malcolm Ranson

ROYAL SHAKESPEARE COMPANY

William Shakespeare’s King Lear was first performed 400 years ago and the tragedy of King Lear remains one of the greatest plays in world drama, as Shakespeare investigates old age, mortality, family and man’s need for religious belief and the capacity to endure.

Previous RSC Artistic Director Trevor Nunn returns to the Company to direct an ensemble company in King Lear and The Seagull.

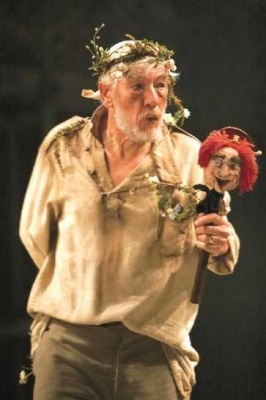

Ian McKellen returns to the Royal Shakespeare Company after 17 years to play the title role in Shakespeare’s epic tragedy. “Ian McKellen is a majestic, moving Lear… triumphant” – The Guardian

Sylvester McCoy, perhaps best known for his performance as Doctor Who, re-joins the company to play The Fool having last appeared for the RSC in The Lion The Witch and the Wardrobe, while William Gaunt plays Gloucester in King Lear and shares the role of Sorin in The Seagull with Ian McKellen. William’s recent stage credits include Humble Boy, Albert Speer and The Cherry Orchard, all for the National Theatre.

returns to the company to play Regan having recently played Jane Eyre for SharedExperience and Lady Macbeth for Out of Joint. She last appeared for the RSC as Katherine in The Taming of the Shrew.

“King Lear ranks with Trevor Nunn’s best work, and Ian McKellen now enters the pantheon of the greatest Lears of the past 50 years… The company acting is impeccable” – Sunday Times

WELLINGTON

Where: Westpac St James Theatre, Wellington

When: Saturday, 11 August 2007 – Monday, 13 August 2007

Times: 7pm

Cost: Buy Tickets

AUCKLAND

Where: Aotea Centre, THE EDGE, Mayoral Dr, Auckland, Auckland

When: Saturday, 18 August 2007 – Saturday, 25 August 2007

Times: Sat 18, Tues 21, Wed 22, Fri 24 Sat 25 7pm

Cost: Buy Tickets $50-175 0800 TICKETEK

PERFORMERS

Ian McKellen

Sylvester McCoy

William Gaunt

Monica Dolan

Romola Garai

Frances Barber

Julian Harries

Guy Williams

Philip Wincheste

Ben Meyjes

Jonathan Hyde

William Gaunt

MUSICIANS

John Gibson, Jeff Moore, Adam Cross and Steve Walton

Theatre ,

Uneven performancess diminish excellence

Review by Kate Ward-Smythe 20th Aug 2007

We open and close with composer Steven Edis’ powerful organ music, not unlike Bach’s Toccata in D minor, played live by one of four musicians (John Gibson, Jeff Moore, Adam Cross and Steve Walton). Throughout the evening, this quartet plays impeccably.

Neil Austin’s lighting is flawless. He captures the detail and nuances of the players, as well as adding exquisite details of his own, such as incidental shadows of dancers and light entertainment elsewhere, as deceit unfolds downstage.

Designer Christopher Oram’s costumes ooze opulence and inspiration into an increasingly bleak landscape. The men are striking, often in strong black and gold and the woman appear in the most beautiful, glamorous, full dresses. Grey and silver never looked so stunning.

Oram’s set, an ornate and vast balcony, adorned with velvet drapes, looks far away and foreign against the modern frame of the Aotea Centre. How different it would’ve looked and felt, housed in the Mighty Civic. In addition, the balcony is under utilised, reducing it to little more than a façade. By contrast, a huge forestage, jutting into the Aotea stalls, brings the players among us and through us, via exits and entrances, and is far more effective.

The fight scenes, designed by Malcolm Ranson, are highly physical and well choreographed.

While McKellen is an absolute stand out, the cast overall deliver mixed performances.

From his opening line, Ian McKellen is tangible, inspiring and superb. My impression is McKellen came to his Lear with his heart and mind wide open, endowing our flawed King as a man full of genuine love, loyalty and great leadership, undone only by an old man’s flippant foolishness.

Two of Lear’s daughters give him plenty to play against.

The porcelain features and steel gaze of Frances Barber’s Goneril set her aside instantly as a calculating ice queen not to be trifled with. However, while her clipped articulation is commanding, as she crumbles to her end, her muted cries seem to reveal more broken voice than raw emotion.

Monica Dolan’s feisty Regan is less concealing with her ambition, yet through subtle mannerisms and increasingly alcohol-fuelled reactions, she effectively shows how quickly greed can consume one’s mind.

Regrettably, given young Cordelia’s stand against her father’s folly, both physically and vocally, Romola Garai does not exude the inner strength or resolve such a bold yet well-motivated act of defiance would require.

While many of the male leads, such as Julian Harries and Guy Williams, as the Dukes of Albany and Cornwall respectively, deliver in excellent voice and manner, again there are some frustrating performances. Philip Winchester, as the villainous Edmund, is more smug mannerisms than scheming malice; and while Ben Meyjes as Edgar gives a solid performance, he, like so many male cast, resorts to yelling and screaming at, and over, his fellow cast members, to attempt emphasis.

Not so Jonathan Hyde, who as the Earl of Kent, gives an intelligent pace and pitch to Kent’s journey. William Gaunt’s gentle Earl of Gloucester’s best scene is in the arms of Lear. As the two cast-outs lament the wickedness of their cruel children, their bond of fatherhood is achingly raw and moving.

Sylvester McCoy is a crowd pleaser, throwing everything at the role of Lear’s Fool: energised slapstick, witty ventriloquism, song, spoons and ‘dick-jokes’. His moments of truth are just as sharp, and his untimely end, shocking.

King Lear is a potent mix of madness and mortality; the extremes of the human condition; and the faith and fate of a family pulled apart by greed, lust for money and power. There is such an excess of wrongdoing and bad behaviour in Lear; it has the potential to overwhelm the senses.

Yet by the end of this production, my senses remained intact. Aspects felt too restrained. For example, New Zealand well knows bad weather, capable of taking a life. Nunn’s staging of the raging storm restricted the player’s movement, reducing what should have been howling wind, driving rain, deafening thunder and blinding lighting, to an under-whelming light shower in the middle of the stage. Secondly, at times during the evening, as treachery and madness take hold, Oram’s set begins to fall apart. Yet similar to the storm, the disintegration is almost tidy. I wanted to see the idea fully explored, with the facade crumbling completely, till it was unrecognisable rubble.

But more than either of these moments, for me, it was the uneven performances that diminished this otherwise most excellent production.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Star performance should have shone brighter

Review by Laurie Atkinson [Reproduced with permission of Fairfax Media] 13th Aug 2007

Not since Laurence Olivier played Richard III at the St James in 1948 can there have been so much excitement for a classical theatre company as there has been for The Royal Shakespeare Company’s King Lear with Ian McKellen in the lead. The opening night full house was not disappointed, giving the company a standing ovation.

Trevor Nunn has chosen to set Lear in the nineteenth century in a country somewhere between Russia and Ruritania. This ‘Albion’ is ruled by a despot who is part Tsar and part uncouth Cossack who strikes Cordelia, floors Kent with a right hook and crudely nudges Albany suggesting it’s time Goneril was pregnant.

Russia/Ruritania is established by a permanent setting of an imposing palace balcony (or is it a theatre?), which slowly disintegrates as the war destroys the land. However, it is used only once by the actors and it detracts from the scenes when Lear is reduced to nothing on the heath, despite all the misty rain and ear-splitting thunder.

The costumes are rich and gorgeous with Cordelia dressed at the start much like a juvenile lead in an operetta and Goneril and Regan always appearing as if they are off to a ball whether they are on a battlefield or torturing an old man. The operetta-like music between the earlier scenes, while in period, is too cinematic and obtrusive.

Though the humour and the pathos of the Fool scenes (played as a spoon tapping vaudeville act), are largely lost, one of the pleasures of this production is the laughter that is to be found in this tragedy. The orchestrated abdication scene starts with Lear reading badly from cue cards his speech in which he demands his daughters to tell him how much they love him. When Cordelia fails to play along with the game, Lear at first gently ticks her off but when she remains resolute, the explosion of Lear’s anger is truly shocking and it is not surprising that the court falls prostrate on the floor.

No doubt warned of the complaints about the lack of projection by the cast of The History Boys at the St James last year, the RSC actors speak with great clarity and volume, some straining, some declamatory, some chopping up the lines haphazardly, and others like William Gaunt (a strong Gloucester) clear as a bell and not forcing the meaning or the metre.

Towering over the production is Ian McKellen’s superb Lear. His performance is full of wonderful moments (cradling and kissing Gloucester like a baby), startling readings of lines (the howl he emits over the dead Cordelia becomes an order to Kent to howl too) and the emphasis on certain words (the terrifying stress given to ‘born’ in "Better thou hadst not been born …").

His descent into madness is marvelously plotted. His stumbling walk towards Goneril as Lear curses her and the threat to create the terrors of the earth are somehow able to covey both Lear’s anger and an awareness that he is being foolish.

The final scenes of Lear’s odyssey to acceptance and reconciliation are beautifully played out and left me admiring but unmoved. I felt I had witnessed a star performance that should have shone even brighter than it did but was prevented from doing so by a production and a supporting cast that only intermittently blazed as brightly.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Palatial disintegration dramatises Lear’s demise

Review by John Smythe 13th Aug 2007

In the St James, the long, curving and ornate balcony of the palatial set could be an extension of the theatre itself. Although the play is set in Britain, heading inexorably to Dover, the costumes take this Trevor Nunn-directed Royal Shakespeare Company production of Shakespeare’s King Lear, designed by Christopher Oram, further east into Europe: Tsarist Russia, perhaps? Some scenes into the play, a soldiers’ Cossack dance seems to confirm this.

Revolution is in the air, then, and it’s important to note that wealth and power, or the desire for it, equates with evil while goodness comes to those who renounce worldly goods, become like the common folk, confront nature in all her fury and align with the elements. But the top-down hierarchy of the abdicating King Lear’s realm is threatened not by civil unrest but by the opportunistic flattery of his deceitful older daughters, Goneril and Regan, who – with their husbands the Dukes of Albany and Cornwall – are greedy for land and power. This challenge to the natural order brings the drama closer to the ancient Greek tragedies of Sophocles, Aeschylus and Euripides.

Indeed there is no Christian orthodoxy in the text. Appeals to Apollo, Jupiter and "the gods" rather than "God" retain the pre-Christian ethos of the actual King Leyr’s Britain, anonymously dramatised as The True Chronicle Historie of King Leir in the 1590s, a few years before Shakespeare penned his version, in the wake of Guy Fawkes’ gunpowder plot, and when King James was attempting to unite the sovereign realms of England and Scotland into a new nation called Great Britain.

In revisiting this fable of a kingdom divided, Shakespeare chose to change the King Leir ending – where a just and merciful God rewards the good by sparing the life of the honest daughter, Cordelia, and restoring the king to his throne – to a fully tragic outcome where Cordelia is hanged in prison just before her pardon comes through, and Lear dies of a broken heart with her lifeless body in his arms. Perhaps the playwright was casting himself as King James’ "all licensed Fool", sounding a note of caution not so much to him as to those who opposed him.

"The weight of this sad time we must obey," Edgar – the good son of the late and good Duke of Gloucester – advises us, amid the corpses of Lear and his daughters; "Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say." And now, in a world where political spin obscures all truth and – in the name of one god or another – ruthless acts are committed daily in the quest for land, resources, wealth and power, King Lear cannot help but resonate with our own lives and times.

As with the Bacchanals-Fortune King Lear (reviewed last week), a prologue sequence precedes the expository chat between Kent, Gloucester and Edmond with which Shakespeare starts his play. The B-F production brings a blindfold Lear into his surprise birthday party, giving us ready access to his status as a lovingly indulged father. For the RSC, Lear presides over a ritualistic gathering of loyal subjects, bestowing grace and favour in a manner that clearly places him at one remove only from the all-powerful gods. While this makes him more remote from the groundlings, it also sets him up with a longer way to fall, in order to attain the wisdom his journey through madness will bring.

Ian McKellen tracks the epic journey from unilaterally powerful King to dispossessed outcast through brainstorm and madness to wiser Fool – finally carrying his hanged Fool’s bauble of office – with great authority, authenticity and humanity. He marks the moments of change with a deep-felt truth and clarity that communicates profoundly, no matter how soft his voice or subtle his actions. Despite the character’s despotic flaws, he commands our empathy and moves us deeply.

With an undemonstrative confidence, William Gaunt shares the Earl of Gloucester’s parallel journey (deceived by his bastard son Edmund into turning against his legitimate heir Edgar, then accused of treason and blinded, making the trek to end it all off the cliffs of Dover, guided and saved by Edgar, disguised as the ‘madman’ Poor Tom, only to die too of a broken heart). It’s admirable, yet I am somehow less moved by his performance than I have been by others.

Sadly for the balance and tone of the production, Romola Garari shouts rather than projects her lines and gestures wildly as Cordelia, denying us any real insight into her true nature. A tendency to lean forward for emphasis also dilutes any sense of her inner strength of character, and suggests insecurity in the role. Jonathan Hyde’s Earl of Kent exudes physical fitness but alienates our empathy by declaiming his lines in the unmodulated tenor tones I equate with the limitations of opera acting.

Ben Meyjes grounds Edgar as a bookish man of integrity but allows his Poor Tom to resort too much to shouting, missing the chance to draw us into the pathos of his plight, let alone explore the metaphysics of so-called madness. Pathos is also missing from Sylvester McCoy’s Fool, who nevertheless plays the vaudevillian with classic timing, a strong singing voice and a clear sense that his place in life is to accept fate as it comes.

On the dark side, character-wise, Philip Winchester articulates the scheming, manipulative, status-hungry Edmund clearly enough but lacks the charm or charisma to seduce us towards taking his side. The lustful attraction both Goneril and Regan feel for him is therefore presented as a matter of objective fact, with which we are unable to empathise.

Frances Barber’s gracefully comported Goneril is largely the declaiming actress, albeit beautifully spoken and clear as a bell, but she does nail key moments of emotional truth to powerful effect. Monica Dolan more completely inhabits the role of Regan, revealing a dangerous spoilt-brat delight in the eye-gouging scene (which I have to say is not a patch on the Bacchanals-Fortune one for gut-wrenching shock-value).

Guy Williams’ Cornwall is the despot he needs to be and Julian Harries, John Heffernan and Ben Addis give sound readings respectively of Albany, Oswald and the King of France (who weds Cordelia despite her lack of dowry), but I have seen others reach more eloquently beyond the spoken text to reveal their feelings for their respective spouses or lovers, and about the unfolding events.

Maintaining the palace as a constant setting that slowly disintegrates, and fades or comes forth as illuminated by Neil Austin’s superb lighting design, has the dual effect of dramatising the demise of the old order and pointing up the proposition that Lear’s journey is more through his mind than a literal landscape. The actual misty rain, however, dropping gently as it does upon the outcasts as Fergus O’Hare’s stunning sound design rends the heavens, is a poor substitute for the hard-driving angular torrents we would readily have conjured in our imaginations from the textual descriptions (not least because most of us braved such a storm to get to the opening night in Wellington).

The full-frontal exposure of McKellen’s Lear to the elements cannot pass without scutiny. Aside from the fact that, in the foyer after the show, round-eyed women shared their whispered wonderment at the generosity of his endowment, bemoaning the fact that its owner was gay, while their men-folk looked the other way or cracked gags about his being better hung than the Fool or Cordelia, the actual staging of this event bears further consideration.

During the storm on the blasted heath, Lear encounters the near-naked ‘Poor Tom’ and is shocked by his exposure to the elements, yet impressed by his lack of debt to the worm for silk, the beast for hide, the sheep for wool and the cat for perfume. "Thou art the thing itself: unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art. (Tearing off his clothes) Off, off, you lendings! Come, unbutton here." It is scripted, then, that Lear at least begins to disrobe, as the Fool cautions him that "’tis a naughty night to swim in" and Gloucester’s arrival interrupts the flow.

But in this production Poor Tom is on his back and Lear is holding his ankles high and wide, and gazing at his crotch, while describing him as "a poor, bare, forked animal". So when he drops his trousers first off, still gazing a the "fork", it seems as though Poor Tom is about to be "forked" indeed! Except Lear’s lack of tumescence makes this a forlorn desire on his part and a lucky escape for Tom. Is it the poignancy of impotence the production is hoping to suggest, or has it hijacked its own desire to simply show Lear totally stripped of all his possessions?

As with the Bacchanals-Fortune production, the RSC King Lear delivers the play with a clarity that has impressed many who have, in the past, been confused and bemused by its convolutions. Also remarkable for a New Zealand audience is to witness a production that employs a fully professional cast of 27: about thrice the number our companies can manage before doubling and tripling roles (as Shakespeare’s company did) and bringing in students on work experience to play bit parts. While it is interesting to note how good the RSC actors are at standing stock still and remaining attentive, in large groups, while the leads play out a scene, I cannot say that is an improvement on the ingenuity with which our companies work around that lack of numbers.

These players are welcome to Wellington and Auckland. We are certainly the richer for seeing them and McKellen especially deserved his standing ovation. But I do want to impress on theatre-goers that if you have paid the prices asked for King Lear and The Seagull (being played in repertoire by the same company), at the expense of patronising local productions, you may well be the losers.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments