LUCRECE

TAPAC Theatre, Western Springs, Auckland

26/10/2016 - 29/10/2016

Production Details

The hotly anticipated debut show from the Auckland Shakespeare Company has arrived. After four years of grooming young actors and receiving critical acclaim for their annual youth shows, ASC has chosen 2016, the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare, to launch their first professional production: LUCRECE.

In a bold departure from the usual Shakespearean fare of large casts and well known texts, ASC brings you LUCRECE: a reinvention of Shakespeare’s darkest narrative poem, The Rape of Lucrece. Working from the original text, a chorus of four actors take you on the heart-stopping journey of Lucrece, the chaste wife of a noble lord, who is sexually violated in her home by Tarquin, a Roman Prince. As a result she commits suicide and her body is paraded through the streets of Rome.

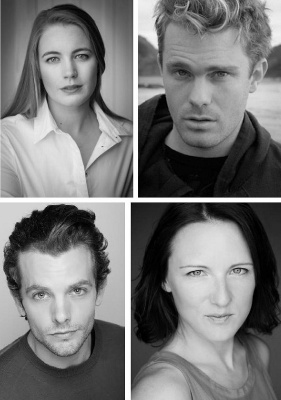

Don’t miss this intense and confronting nightmare based on a 400-year old poem that explores themes more relevant now than ever, under the expert direction of Auckland Shakespeare Company’s Artistic Director, Rita Stone, with actors Anthea Hill, Daniel Watterson, Sheena Irving and Calum Gittins, and original music composed by Paul McLaney (“…on the threshold of something big” – Mike Alexander, Stuff).

Warning: contains themes of rape and suicide

“I don’t often say this but I simply can’t wait to see what this talented, capable, and dedicated bunch do next.” – Lexie Matheson, Theatreview

TAPAC (The Auckland Performing Arts Centre, 100 Motions Road, Western Springs)

Wednesday 26 October – Sunday 30 October 2016

Tickets: $20 – $39

Book: www.tapac.org.nz or 09 845 0295

CAST:

Daniel Watterson

Anthea Hill

Calum Gittins

Sheena Irving

David Capstick

CHORUS:

Zach Buckland

Steve Austion

Vincent Feng

Reuben Bowen

Edward Peni

CREATIVES:

Rita Stone: Director

Paul McLaney: Composer

Brigitte Knight: Choreographer

Amber Molloy: Lighting Deisgner

CREW:

Mary Rinaldi: Producer

Jonathon Wilce: Stage Manager

Steve Austin: Assistant Stage Manager

Duncan Milne: Operator

Jamie Blackburn: Set Construction

Eve Gordon/ Dust Palace: Aerial Trainer

Adam Baines : Photographer

Benjamin Brooking: Promotional video

Sash Nixon: Boosted Campaign video

Katharine Harding: Poster Design

Theatre ,

A hugely impressive achievement

Review by Leigh Sykes 27th Oct 2016

As Rita Stone points out in her Director’s Notes, “turning a narrative poem into a viable, full-scale theatrical production for four actors and a Greek chorus [is] uncharted territory” but Stone and her team should be congratulated for the fine job they have done in charting the unexplored and creating a satisfying and truly theatrical experience.

On entering the performance space some non-naturalistic aspects of the staging are clear, with ropes hanging in the four corners of the space and a swing near the centre. Echoes of Peter Brook’s 1970 A Midsummer Night’s Dream spring to mind, along with the anticipation that this production will pay just as much attention to the clarity and intention of the verse as that one did.

From the very beginning the audience is addressed directly and invited into the world of the play through Reuben Bowen’s delivery of Shakespeare’s ‘argument’: an introduction to the poem that acts as a prologue, telling us the major events of the story we are about to witness. Shakespeare does this to great effect in other plays and here it serves to begin the process of familiarising us with the language of the piece, which is rhythmically very regular (very typical of Shakespeare’s earlier plays), and where echoes of plays written in a similar time period (such as the description of Lucrece late in the piece as “key-cold”) can be found.

Bowen does a good job of grabbing and holding our attention in this section, and lays the foundation for the later role of the Chorus when he puts on the mask waiting for him and instantly transforms into a very different, otherworldly creature.

The first section of the play splits the narrative between the characters of Tarquin, a Roman Prince (Calum Gittins), Collatinus, Lucrece’s husband (Daniel Watterson) and Lucia, Lucrece’s Lady’s Maid (Sheena Irving). It takes me a little while to get used to the way the verse is shared out, with one or two moments delivered in unison.

Lucrece (Anthea Hill) spends much of this time on display on the swing as the other characters describe and talk about her. She is extremely objectified here, posing for our view and exemplifying the virtues ascribed to her, and this is where the modernity and relevance of the subject matter first begins to be apparent.

Both Watterson and Irving have a sure grasp of the language here, but for me Watterson stands out with the clarity and delivery of the language and the thoughts informing this, as well as with the connections he makes with the audience. We glimpse moments of Collatinus and Lucrece as husband and wife in this section, laying a foundation against which we can judge the events that follow, and Watterson shines with the way he displays a deep connection with Hill’s Lucrece.

The play steps up a gear as Tarquin reaches his decision to give in to his lust and go to Lucrece’s chamber to ravish her, while Collatinus and Lucia watch, perched on small platforms suspended from the ropes that frame the space. It strikes me that having these characters suspended above the action in this way hints at voyeurism, but it is also very effective in allowing us to see clearly their responses to the events that unfold; events that they must describe but which they cannot stop.

I particularly like the use of the Chorus in this section. Their masks and sharp, angular movements make them seem very alien and forbidding, as they too try to stop Tarquin’s progress towards Lucrece, only to fail. When Tarquin and Lucrece come face to face, the play really takes off, as the characters and the impending events become more real through this dialogue.

Gittins does an admirable job of making Tarquin’s battle between self-loathing and resolution believable as he strikes terror into Lucrece, and the poem is mined very skilfully here to give these characters their voices. As Tarquin blames Lucrece’s beauty for his actions, I feel many echoes and connections to other Shakespeare plays (Richard III blaming Lady Anne’s beauty for the murder of her husband for example), but also to 2016, where so many women are routinely told that they have provoked the monstrous events that have happened to them by the way they have dressed or behaved, and where young women are told that they must take responsibility for not distracting young men by wearing school uniform modestly. This blame culture is insidious, and it is apparent that Shakespeare has been making this plain for over 400 years.

The attack on Lucrece is staged sensitively and effectively, allowing us to focus on the aftermath of the event. Throughout this sequence both Gittins and Hill display a clarity of language and action that supports the narrative well. Although I sometimes feel that the delivery of the verse is a little ponderous, this does not detract from the fact that the actors display a deep understanding of the verse.

Hill has a difficult job to do in this long section, where sustaining the level of emotion becomes physically demanding and quite repetitive, and on one or two occasions I feel her vocal performance lacks subtlety and variety. Gittins works equally hard during this section and succeeds in making us despise his actions in a role that is designed to be appalling.

The aftermath of the rape continues to resonate with modern circumstances as Lucrece is forced to recount the details of her attack so publicly, before shockingly taking her own life.

I find that the most affecting performance moments for me are small ones such as Watterson’s silent but impassioned responses to Lucrece’s impending doom and his failed attempts to protect her; Irving’s grief at what has befallen Lucrece and David Capstick as Lucretius (Lucrece’s father) responding to his daughter’s death. These moments of reaction draw us further into the story and make the human cost of the events plain.

Music (composed by Paul McLaney) is used throughout the piece, and although sometimes the sound level seems slightly loud and comes close to overwhelming the dialogue, the tone and quality of it supports the play extremely well. The use of songs can sometimes feel jarring, but perhaps this helps us to take more notice of them and pay attention to these moments of heightened emotion.

The use of a projection on the back wall of the set (constructed by Jamie Blackburn) doesn’t really add anything to my sense of the piece, and while the costumes (no credit in the programme) do a good job of referencing both the ancient (Greco-Roman influenced dresses for the female characters) and modern (sharp suits and shirts for the male characters), some of them are a little unforgiving for the actors.

However none of this really detracts from the thrill of hearing this work for the first time and really having to pay attention to the language. It brings us closer to the way an original Shakespearean audience responded to the plays, experiencing a new work by listening closely.

Stone’s direction of the piece is assured, allowing the language and the performances to breathe, while driving the narrative forward with pace. This is a hugely impressive achievement, creating a dramatic, strong narrative supported by committed performances.

Experiencing this show is an opportunity that should grasped and savoured.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments