Maui - One Man Against The Gods

Civic Theatre, cnr of Queen Street & Wellesley Street West, Auckland

18/04/2007 - 29/04/2007

02/05/2007 - 06/05/2007

09/05/2007 - 13/05/2007

Production Details

Director . . . . . . . . . . . . .Tanemahuta Gray

Choreographer . . . . . . . Merenia Gray

Assistant Director . . . . .Geoff Pinfield

Climbing Director . . . . . Nick Creech

Kapa haka . . . . . . . . . . . Tanemahuta Gray, Kereama Te Ua, Kura Te Ua, Tuirina Wehi

Music

Composer . . . . . . . . . . . . Gareth Farr

Nga taonga puoro . . . . . . Richard Nunns

Additional Music . . . . . . . Ross Harris, Witi Ihimaera

Vocal Director . . . . . . . . . .Louise Clark

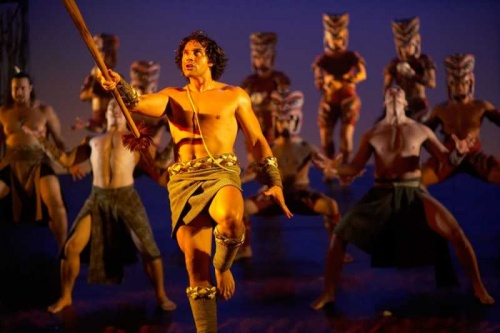

Stirring kapa haka and spectacular aerial theatre unite in this stunning theatre production that tells the story of Maui’s life – a thrilling journey of the senses in which gods fly and one man defies them all. Join 27,000 New Zealanders who have already been enchanted by Maui – One Man Against The Gods.

Maui is the story of a rebel. An outcast young warrior, reared in miraculous circumstances, grows up away from his family and from the norms of his people. Upon returning, he refuses to accept the social and natural limitations of his world. Daring to think big and possessing the charismatic talents to realise his ambition, Maui repeatedly challenges his surroundings as he strives to impose his will on the world.

From the moment of his birth, Maui is marked for both greatness and tragedy. As he steals the secret of flame from the goddess of fire, pulls land from the bottom of the ocean and traps the god of the sun, his achievements begin to transcend mortal limits. Yet, even as he artfully accomplishes these feats, his own sense of glory tragically drives him to challenge the limits of mortality itself.

Staged over 2 hours with a cast of 20 performers, Maui is a dynamic mix of kapa haka, aerial theatre and contemporary dance with an original score featuring traditional Mâori instruments.

See Maui live on its 2007 North Island tour of New Zealand—

AUCKLAND: 18-29 April, The Civic at THE EDGE®

HAMILTON: 2-6 May, Founders Theatre

WELLINGTON: 9-13 May, Westpac St James Theatre

Book at Ticketek. More information is available at www.mauitheshow.com

Story & Lyrics

adapted from the legends of Maui, as told in the oral traditions of Aotearoa (New Zealand)

Stageplay . . . . . . . . Andre Anderson, Tanemahuta Gray, Geoff Pinfield

Te reo Mâori . . . . . Mere Boynton, Greg Crayford, Tanemahuta Gray, Tiahuia Gray, Haunui Hepa, Toni Huata, Tamati Patuwai, Wilson Poha, Toa Wäka, Tuirina Wehi

Dramaturgy . . . . . . Philippa Campbell, Hone Kouka

Design

Set . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Tolis Papazoglou

Costumes . . . . . . . . . . . Gillie Coxill

Lighting . . . . . . . . . . . . Martyn Roberts

Costume Carvings . . . Winiata Tapsell

Cast & Climbers

Maui . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Tamati Patuwai, Jason Te Patu

Hine-nui-te-Pô . . . . . Toni Huata, Olivia Violet Robinson

Tama-nui-te-Ra . . . . Te Kohe Tuhaka, Tamati Patuwai

Taranga . . . . . . . . . . . Kirsten Te Rito, Toni Huata

Brothers . . . . . . . . . . Maaka Pepene, Matu Ngaropo, Jacob Tamaiparea, Jason Te Patu, Kereama Te Ua, Te Kohe Tuhaka

Ensemble

Sacha Copland, Jack Gray, Carrie Lawrence, Claire Lissaman, Maaka Pepene, Olivia Violet Robinson, Taiaroa Royal, Kura Te Ua, Tuirina Wehi, Liana Yew

Aerialists

Sacha Copland, Pipi-Ayesha Evans, Claire Lissaman, Taiaroa Royal, Jenny Ritchie, Alexandra Sim, Kura Te Ua, Tuirina Wehi

Climbers

Kester Brown, Nick Creech, Aaron Grant, Tom Hoyle, Craig Hanham

Technical

Costume Construction Gillie Coxill: Get Frocked, Spaceworks: Frank Cowlrick, Zoe Fox, Cathy Harris, Sarah Muir, Emily Smith

Set Construction Stage Right: Simon McMillan,Dave Barltrop, Darlene Bennett, Craig Hanham, Debs Ruffell

Sound Glen Ruske: Redd Acoustics

Crew

Stage Hands: Melinda Brown, Daniel Christensen, Sam Stuart

Lighting Operator: Darren McKane

Sound Operator: Ben Rentoul

Props Manager: Tim Kaye

Wardrobe: Zoe Fox, Sarah Muir

Tikanga Mâori

>

Kaumatua . . . . . . . . . . Sir Tipene O'Regan

Kuia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Tiahuia Gray, Vera Morgan

Advice Te reo Mâori Te Taura Whiri i te Reo: Hâmi Piripi, Tama Kirikiri, Lee Smith

Management

Creative Producer . . . . .Andre Anderson

Executive Producer . . . .Richard Boon

Stage Manager . . . . . . . .Mandy Perry

Technical Manager . . . . Andrew Gibson

Wardrobe Manager . . . . Zoe Fox

Marketing

Design DNA

Publicist: Sally Woodfield

Photography: Diederik van Heyningen, Nick Servian, Colleen Tunnicliff, Leon Rose

TV Commercial: Rob Sarkies, Raewyn Humphries

Website CSolutions: Richard Berridge

Pilot Production: Te Ao Marama - 19-22 February 2003, The Awakening World, Te Whaea Theatre: National Dance and Drama Centre, Wellington

World Premiere: Westpac St James Theatre, 25 May - 5 June 2005, Chief Executive: Celia Walmsley

2007 North Island Tour:

Auckland: The Civic, The Edge®

Hamilton: Founders Theatre

Wellington: Westpac St James Theatre

Theatre , Kapa Haka theatre , Music , Physical ,

A wonderfully engaging and creative spectacle

Review by Melody Nixon 17th May 2007

Maui: One Man against the Gods is a storytelling spectacular in which the legends of Maui are interpreted through dance, music and theatricality. The effect is an evening of powerful and visceral beauty and emotion, as well as a too rare opportunity to view a professional show presented mostly in Te Reo Maori.

The production is very much a spectacle, impressing its audience with powerful set, sound and lighting design. Such elaborate visual effects might detract enormously from a production if too overdone; fortunately here they serve to prove the consummate experience of the crew involved.

While the whole show could be called a visual kai, certain scenes remain embedded in our imaginations long after. The representation of the thighs of Hine, the goddess of darkness, and Maui’s capture therein, is gorgeously dark, with a powerfully expressive use of bodies and dance. The third, underwater scene is an earthy, raw experience that contacts with us directly through the skin. Aesthetically the colour, movement, lighting and music work to create a harmonious vision that is both dreamy and soothing.

This said, at times the build up of action and effects at the beginning of Maui is a little relentless, and more pause or slowing down could be used in the first four scenes to reduce what becomes a too prolonged and heightened tension. As in the scene of dialogue between Maui and his father at the beginning of Act Two, further moments of quiet reflection – either as dance, dialogue or song – could serve to relax the audience, and make the next moment of deep emotion and power all the more affecting. Furthermore, the occasional spot back-lighting is quite blinding, and while this in itself is not unwanted it means we miss the next few seconds of action while our eyes readjust.

However, overall lighting design by Martyn Roberts is brilliantly emotive. The wide-reaching musical score, composed by Gareth Farr and directed by Louise Clark, is also very moving. It combines classical, instrumental, vocal and modern styles; the hip hop piece at the beginning of Act Two is particularly engaging. The harmonizing in the waiata between Maui and his mother in scene six is chilling and uplifting; and leaves us wanting more of the same. Creatively costuming by Gillie Coxhill, a hybrid of traditional arts and modern fabrics, also assists to stimulate and entertain, particularly in the case of the mesmerizing headdresses worn by the ensemble.

The use of theatre space is another very striking aspect of the show; the split stage is raised at the rear, and so provides a sloped area for actors to utilize vertical as well as horizontal space. This assists the movement towards non-European modes of storytelling, aiding the play’s spiritualism and magic realism, and allowing us to more readily receive its tale. The effect is further enhanced by the team of ‘aerialists’; Sacha Copland, Pipi-Ayesha Evans, Claire Lissaman, Jenny Ritchie and Alexandra Sim. These hanging dancers are suspended alternately above crowd and stage, twirling and spiraling as nymphs, flames and tupuna; often breathtakingly seductive.

The twelve scenes are interlaced with spoken interludes, in which sun-god Ra (Te Kohe Tuhaka) narrates the story in English. While Tuhaka’s voice is a little muffled at times, these interludes do much to aid understanding for the non-Maori speaking members of the audience, as even those of us with a reasonable knowledge of the legends of Maui need to turn to the storyline pamphlet given out at the beginning. This is partly because the retelling of the stories has ventured away from some of the more conventional interpretations we may have been taught. For instance, in the show the ‘capturing of the sun’ to slow its progress through the sky is retold as a very personal battle between Maui and his adoptive father, Tama-Nui-Te-Ra.

On the night I attended Jason Te Patu played Maui, the “man, determined to become a God.” Te Patu’s performance was primarily striking for its dance and physicality, though strengthened by his versatility in kapa haka techniques such as taiaha and haka. Te Patu also brought important elements of comedy into the production, especially in the scenes between brothers. The friendly rapport of Kereama Te Ua, Jacob Tamaiparea, Maaka Pepene and Matu Ngaropo formed a solid backbone of support for Te Patu’s role, their strong, ‘big’ acting always making the meaning of the situation clear to non-Te Reo speakers.

Toni Huata as Hine-Nui-Te-Po dazzled us with her voice, and her machinations at the rear of the stage invariably created an atmosphere of beauty and darkness. Kirsten Te Rito as Taranga performed the night’s most beautiful solo piece when lamenting the loss of her son for the second time, and provided important moments of insight into the real and painful human aspect of the Maui story.

All in all, Maui: One Man against the Gods is a wonderfully engaging and creative spectacle. Constantly being refined and modified, the show has so far endured for four years from its pilot production. Let’s hope it will continue to evolve and grow, and remain a show New Zealanders support and encourage, for years to come.

Originally published in The Lumière Reader.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

An epic story of here, made here

Review by Lynn Freeman 17th May 2007

Tanemahuta Gray shares some of those great qualities with his leading man, Maui – he’s bold, courageous and unstoppable. This stage spectacular, and spectacular it is, has taken years to create and now to refine.

This is the third version of Maui I’ve seen, starting with a few scenes at Toi Whakaari as part of a Fringe Festival long ago. It had promise but where would they find the money to realise that promise? Version two was impressive but a little rough in places and needed some kind of narration to open it up to non-Te Reo audiences. Maui is now a polished and breathtaking show and must surely be destined for the West End and Broadway.

One of the most important changes is the introduction of a narrator – Maui’s adopted father, Tama-Nui-Te Ra, played with godlike majesty by Te Kohe Tuhaka. Even with the very good English plot synopsis given to the audience, he helps keep non-Te Reo speakers on track, and his own near downfall is more poignant for knowing how much guilt he feels over Maui’s actions.

Tamati Patuwai is a force to be reckoned with as Maui, always with a sense of mischief and naivety as he challenges the elements and the gods – he’s more of a naughty boy than a hero and more endearing for it. The four brothers work well as a team, much needed comic relief amidst the intensity of the story.

This is as much of a musical as it is a dance/theatre work and the solos in particular by Toni Huata and Kirsteen Te Rito are emphatically operatic in their delivery.

‘Big ups’ to the flymen, who really get this production off the ground.

You’ll never see a more beautiful and dazzling show on this epic scale – it’s got the grace of ballet, the drama of a Greek tragedy, the spectacle of The Lion King, the athleticism of modern day circuses (the aerialists are unreal) and the added bonus of being a story of here, made here.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Defies gravity in every sense

Review by John Smythe 10th May 2007

I said it was ready for the world two years ago (National Business Review, 3 June 2005). "As epic theatrical spectacle," I wrote, "Maui – One Man Against the Gods is phenomenal. Riveting, amusing and awesome, it is also as profoundly insightful as any ancient rites-of-passage myth about an adventurous demi-god confronting the forces of darkness and light. Yet its distinctively Māori pulse, look and feel, rooted in tradition but expressed with contemporary skills and technological flair, bring a new vitality to this very old tale."

The same is true only more so now. The 12-part storyline, published in the programme, is also offered as a free hand-out to all ticket-holders and yes, it’s a good idea to swot up on it before the show starts. The addition of English-language narration – or rather deep-felt retrospection from a father asking himself, and us, if he might have been able to better divert Maui from the path he chose – richly intoned by Te Kohe Tuhaka’s Tama-nui-te-Ra, adds much to the accessibility of the story.

In a world forever seeking the balance between individual and community, where most religions feed on the human hunger for immortality, whole ‘civilisations’ have been built and glorified through humankind’s battles to conquer the forces of nature (and even better, align with them), and medical science keeps finding new ways for us to cheat death for longer, the story of Maui cannot help but resonate.

By utilising kapa haka, karanga, waiata, patu, taiaha and poi to communicate its classical themes through the international language of physical theatre, Maui refreshes these ancient truths in ways that should add the attraction of the exotic for audiences around the world.

Director Tanemahuta Gray – the modern Maui who gets it right because he listens, responds, aligns and realigns his team – claims in a recent interview that the humour is visual. "Slapstick." (Think of those crazy Japanese comedy shows that totally eschew English language.) Even so, it is still possible that people will think they are missing out because they can’t understand the reo that accompanies it. One young woman I spoke to afterwards was delighted that, "as a little whitey girl" she knew what "iti" meant, so got the gag where one of the brother looks up Maui’s skirt and says it’s tiny. But, as Gray says, you get that from the visual action too: it’s universal humour.

After Maui fishes up his ‘ika nui’ (the North Island), the brothers lie lifeless on the shore. "Ka mate, ka mate," they groan then realise they’re alive after all. "Ka ora," they breathe in growing delight. "Ka ora!" This gag may seem like one only Kiwis will get but given the universal recognition of our Ka Mate haka, and the number of times its meaning has been written up, even this is likely to travel.

As I also wrote in ’05: "Gareth Farr’s resonant music, recorded with the traditional instrumental skills of Richard Nunns, evokes the elemental forces that provoke the drama. Gillie Coxill’s costume designs reject the flax skirt and woven bodice look for a contemporary Pacifica feel …" and either I’ve come round to them or she has modified what I saw as "ancient Aztec, Egyptian, Greek and Roman influences" that sometimes jarred. Winiata Tapsell’s tiki heads and other costume carvings teeter on the brink between authentic cultural artefact and tourism kitsch.

"Tolis Papazoglou’s versatile set, edged with a stylised hint of fortified pa, features a vast sloped stage that transforms into steps," I wrote, "allows for pits of fire and accommodates land, sea and sky with an effortless flow." On opening night in Wellington a broken hydraulic hoist meant the slope was unable to open as steps, robbing us of some visual spectacle including a light-created filleting of the ‘ika nui’ effect (representing the bothers’ carving up of the new land). It is a testament to the strength of the core story that the show held together without it.

"A hectare (I’m told) of fabric is ingeniously used to trap the children [between earth and sky], enhance the aerial illusions of flight and floatation, and create oceans, above and below the surface, giant jellyfish, fire, a huge entwined rope and Hine’s massive black skirt. Martyn Roberts’ superb lighting completes the illusions of primal forces engaging with vulnerable and fallible humanity."

As Maui, Tamati Patuwai has an extraordinary capacity to communicate, through body language, his mood, emotions and states of being, be they playful, curious, fearful, arrogant, imperious, ecstatic … Playing his older brothers as a mini gang, Matu Ngaropo, Jacob Tamaiparea, Jason Te Patu and Kereama Te Ua excel equally in their intimidatory posturing and their clowning about.

Te Kohe Tuhaka brings human sensibilities to the sun god Ra and adoptive father of Maui in ways that have particular resonance, given the recent very public debate on how we raise and discipline children. Simply clad to anchor the real-world dimension of the story, Kirsten Te Rito’s mother of five sons, Taranga, shows strength and humour in raising her boys, and heartfelt humanity in dealing with their fates. Meanwhile Toni Huata’s inexorable Hine-nui-te-Po looms and recedes with ominous power, both vocal and visual.

The singing and chanting from principles and ensemble cast alike vibrate to the very marrow, not only thanks to the sound technology of Glen Ruske: Redd Acoustics.

Different people will respond according to their particular interests and cultural perspectives. For me, apart from the rich story content, abiding memories include the white sprites flying and whirling through the air within the auditorium, eerie aerial spectres catching light in the blackness beyond the stage, the stunning underwater sequence, the invigorating waka-on-the-ocean and fishing scene, and the way the golden light of fire so subtly yet graphically morphs to represent blood.

The immediate quest is to tour the show through the USA next year. The behind-the-scenes story of ‘one show out to conquer the world’ exemplifies the value of aligning to what’s so, rather than battling against the ‘gods’. Beyond the artistic qualities and production values, what will get this show there is the reduced company size (37, including 21 cast of which 18 perform each show; 4 climbers to counter-balance the aerialists; mechanists, operators and backstage crew) and their capacity to pack the show into each new venue in a day and a half. And Maui has now achieved that goal.

Maui – One Man Against the Gods defies gravity in every sense of the term. Every New Zealander, immigrant and visitor to our shores should see this show where they can, then alert anyone they know in any part of the world it may travel to.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

A truly significant milestone

Review by Kate Ward-Smythe 19th Apr 2007

Maui, soon to be seen by international audiences, and currently showing in Auckland, has moments of stirring beauty and impressive visual delight. Unfortunately, by comparison with – and competing in the same market as – other epic extravaganzas that draw on aerial theatre and the collaboration of dance, song and spectacle (such as Cirque du Soleil), this work still needs some refinement to reach and "wow" a wide audience.

In a sentence: Maui is the story of a young warrior, raised by the gods, who returns to the natural world and refuses to accept the norms of his people, so imposes his will and power on the world, with tragic results.

There are translation issues for non-Māori speaking members of the audience, as 95% of the script and song, is in te reo. I only knew the broad aspects of the plot (indicative of the new audiences Maui wants to reach) and found myself lost occasionally and detached from the story more than once. Although Ra steps forward occasionally to narrate in English, and Te Kohe Tuhaka has great presence in the role, as well as a rich, warm voice, it is not enough. Before the lights went down, I read as much as I could of the free story line given to me as I entered the theatre, and that helped. But even those I spoke to afterwards, who were more familiar with the legend than me, struggled at times with the language barrier. Sur-titles are used by opera companies to overcome this problem – something for Creative Producer Andre Anderson and Executive producer Richard Boon to consider.

The notable exceptions that transcend the language barrier are scenes between Maui’s brothers, where the ensemble work of Maaka Pepene, Jacob Tamaiparea, Kereama Te Ua and especially Matu Ngaropo, portraying lads enjoyed childhood games and engaged in status play, spoke a universal language. Rivalry and sibling jealousy upon Maui’s return from Ra’s godly kingdom is well communicated. The strong mother-son work between Te Rito and Te patu is also clear and expressive.

As to the rest of the scenes, it is a shame I missed so much, as there is no doubt those audience members fluent in Māori, got 50% more from the production than we did, laughing and applauding in places where I was playing catch up, trying to process what I’d just seen and heard.

Maui affected me the most during intimate scenes between the four strong, well cast lead characters: Jason Te Patu (Maui), Kirsten Te Rito (Taranga), Toni Huata (Hine) and Te Kohe Tuhaka (Ra). In particular, the emotional reunion between Maui and Taranga during the scene "On the beach" is touching, with both actors giving depth, vulnerability and heart to their performances. Te Rito is also strong, during "In the Air", filling the Civic with sadness as she mourns the loss of her son a second time.

The original score (composer Gareth Farr) featuring traditional Māori instruments (played by Richard Nunns) is strong with dynamic flow, but with one notable exception to my ears: the sudden musical gear change into rap | hip hop during "Gone Fishing", seems to come from nowhere and be at odds with the scene established.

The soundtrack level is invigorating; especially during the fight sequence in "Back on the beach", where the music, sound effects and stage fight, blend strikingly.

The quality of the sound (Glen Ruske of Redd Acoustics), as with all Maui’s production values, is excellent. Lighting design by Martyn Roberts is exquisite throughout, with colour creating a new world in each scene – "Under The Sea" is a stand out – but with spots and specials still giving soloists and key action the significance required to draw the audience’s attention.

The air-borne feats of the main cast members and aerialists are fluid, indicative of their skill, and of the craft of the behind the scenes crew. Key moments, such as the entrance of Hine, are inspiring, both on a technical and creative level.

Set design, by Tolis Papazoglou, is a mix of dressed structures to create dynamic shape and height, such as scaffold towers and raked staging units that split open, and traditional materials such as wooden fencing that might be seen around the perimeter of a pa.

However, it is the use of fabric in particular to depict the elements that dominate the overall look. In some cases it is superb, such as the material creation of waka and sea in "Gone Fishing". Another highlight is Hine’s cloak – a stunning, seemingly endless waterfall of cloth. Occasionally, the material is overused, diminishing the overall impact; "In the Cavern of Fire" is a casualty.

Costume design (Gillie Coxill) is a mixed bag. The detail, design and construction of the lead character’s outfits are commendable. In terms of the chorus and dancers, the stand out look for me was the costume carvings by Winiata Tapsell. By comparison, the tattered look of the fire dancers’ costumes is tacky and cheap.

With experienced dancers such as Taiaroa Royal in a cast with mixed abilities, the ensemble work is under very capable leadership. The quartet who feature in "Gone Fishing", is particularly beautiful.

Much of the choreography (Merenia Gray) is stirring, with a good fusion of kapa haka and modern dance, plus inventive moments such as giving macramé a new lease of life on an epic scale. However, the occasional move, like running across stage holding lengths of fabric above one’s head, is dated and at odds with innovation shown elsewhere.

Jason Te Patu, in the lead role of Maui, captures the growth and journey of this daring young warrior very well. During early scenes especially, Te Patu’s physicality and every expression captures the innocence of childhood and a wide-eyed energetic youth, out of his depth in a foreign environment. As Maui comes of age, using his craft and charisma to affect those around him, Te Patu is understated and intelligent in his performance. Yet his strength and fitness make him equality impressive as he unleashes the warrior in "Back on the beach".

Toni Huata brings serene strength to Hine, and shows great focus and vocal control, by continuing to sing with effortless beauty, as she flies across the stage.

While director Tanemahuta Gray and his assistant Geoff Pinfield have achieved an enormous feat, pulling this epic complex work into a cohesive whole, overall, Maui is uneven. Some scenes are flawless, such as "Under The Sea", in which all elements combine for innovative story telling and spectacle. But there is tweaking to be done in other areas. Maui is a truly significant milestone in New Zealand | Aotearoa’s history of large-scale musical theatre cultural collaborations, and sets new standards in this genre.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tihei mauri ora!

Review by Nik Smythe 19th Apr 2007

Much respect is due to the considerably ambitious vision of a driven company, helmed by co-writer and director Tanemahuta Gray (prying New Zealand’s horizons upwards so our poppies can grow tall as nikau?).

The able ensemble cast, including a specially mentioned appearance by legend dance veteran Tairoa Royal, deliver strong performances which frequently are accompanied by a phat electronic soundtrack which I feel at times undermines the stark power of a raw, all out acapella haka. I get a sense of an attempt to widen the accessibility of the piece through inclusion of so many elements – ancient lore, martial arts, wearable art, circus, modern rock opera, kapa haka, hip-hop, and even slapstick comedy relief in Maui’s four brothers.

Jason Te Patu’s softly spoken and beautifully sung Maui* is a babyfaced imp who behaves like any hyperactive kid you might’ve met. His connection with his mother Taranga (Kirsten Te Rito) is touchingly clear, although the sentimental Broadway-style waiata they perform in duet when they meet for the first time upon his return to the surface world is a mite beyond my personal taste.

For audience members not fluent in the Māori language a programme is essential for a cohesive narrative, combined with the English commentary of Tama-Nui-Te-Ra, played with powerful command by Te Kohe Tuhaka on opening night. Having experience with the mythology of Maui may also help, although in a number of ways it differs from the more well known versions.

For all I know Maui – One Man Against The Gods may incorporate more ancient tellings than I may ever have heard, yet this clearly is an original adaptation. Here is a legend retold with homage to the spiritual essence of the old tales, yet choosing to radically reform such key relationships as Maui and Tama-Nui-Te-Ra, the sun god whom Maui comes to snare and beat to submission in the most well-known of all. Ra is now Maui’s adoptive father after his mother, Taranga, cast him to Tangaroa in a lock of her hair when he died in infancy. Also, his mystical weapon is not the jawbone of his grandmother, it is now Tama-Nui-Te-Ra’s sacred patu, appropriated by Maui in his first act of defiance, which he then turns against him in an originally conceived scene wherein Maui delivers retribution upon Ra in retaliation for a prior stepfatherly punishment.

The major treat in Maui is the one they promote it with on television: the rich spectacle of visual composition, in particular Gillie Coxill’s costumes illuminated by Martyn Roberts to wondrous effect and adorning energetic dancers and gymnasts who have the audience gasping with wonder throughout. My favourites are Hine-Nui-Te-Po’s costume and the waka on the sea when Maui fishes up the North Island.

Overall, there were many things for me to like in this cross-cultural extravaganza, and other bits I didn’t so much. At various times throughout the two hour epic I thought I might understand what’s going on here but wasn’t certain that I really did. Much clarity is lost, not necessarily by the language barrier but by a cluttering of elements with no silent, still, quiet breathing moments.

I am very interested in hearing how members of the community fluent in te reo Māori, as well as any known spokespersons for the heritage of Tino Rangatiratanga, feel this project is going, considering the company’s expressed interest in bringing this brand to a global audience. The greatest question is this: is the balance between the soul and integrity of Māori lore and the accessibility required to snare an audience, as only Maui could, a harmonious one?

The most significant concept in the show for me is Tama-Nui-Te-Ra’s statement that Maui was meant for death (the goddess of death, Hine-Nui-Te-Po, is performed with duly haunting power by Toni Huata) since the day he was born, yet circumstance and willfulness enabled him to defy her. This sums up who Maui is to me: the chaos element that is essential to growth and development. And what if Maui had simply died as a baby instead of defying the gods?

To my knowledge, this is the closest thing to a world class show of this scale ever produced in this country. I think to reach that global audience it needs work and the challenge is to find the support required to keep the idea alive enough to work it to the point of truly classic status.

_______________

* The four main parts, Maui, Hine-Nui-Te-Po, Tama-Nui-Te-Ra and Taranga were played by the actors credited in this review on opening night. The parts of Maui and Ra are alternately shared with Tamati Patuwai, Po shared by Olivia Violet Robinson and Taranga by Toni Huata.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments