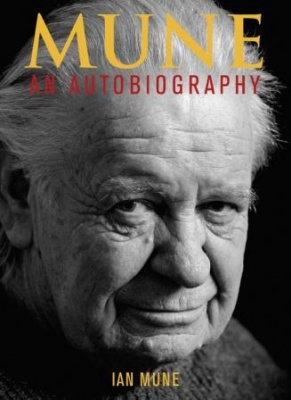

MUNE an autobiography

A bookshop near you/buy online, (not a specified venue)

17/12/2010 - 31/01/2011

Production Details

Ian Mune’s resonant growl and his characterful face are an institution in the world of New Zealand theatre, film and TV. He has been a central figure of screen and stage in this country since the 1960s.

This beautifully written autobiography is hugely insightful about the personal process, the challenges and the rewards of acting. But Ian Mune’s story also has much wider significance, as it provides a fascinating and unique view of the roots and development of contemporary theatre, TV and the film industry in New Zealand.

Published, Nov 2010

Craig Potton Publishing

ISBN 9781877517334

$49.99

A ripping yarn, a page turner

Review by Waka Attewell 27th Jan 2011

Ian Mune is the darling naughty boy of Stage, Movies and TV. He’s bad in that best possible way: he’s bad because he cares. And we love him more for it.

I had the pleasure a few days ago of sitting in a café with him under Mt Taupiri – breakfast – the owner recognised him and we get 3 Neenish tarts for the moment of notoriety… though she had to ask his name… “I know who you are but I can’t remember it,” she said.

Ian smiled and said his name – she then banged him on the arm, “Yeah, I know that.” We all know him, we grew up with him, that was him larger than life.

I have to declare my hand. I still think Moynihan is the best NZ TV ever!

Recently a brick arrived in the mail – a book – the word is out – one of our clan has written it – you cant miss it he’s on the cover. Once described as “a face like an unmade bed…” – it’s actually quite a beautiful face and though the years have wearied the exterior the mind – the wit is still as sharp as a tack. And those eyes have seen a bit… quite a bit in fact.

Opinion and the ownership of it is an interesting subject. Orthodox thinking and toeing the line – Mune says why bother. It’s like you get one go at this life and this is it! I asked him once, “What do you think happens after you die?” He said that “all the pain of this life would be finally gone.” Good answer under the circumstances as we were probably both drunk and probably both a wee bit depressed and did I mention the NZFC which always gets a bit of a hiding under these circumstances?

He writes very well, he writes particularly well about the roller coaster ride of a man who chooses to be an artist in a time when the notion is not even seen as a viable option: 1960’s New Zealand where to be a grey bureaucrat was where ambition came to live and die. It was expected. Being a painter, or an actor or god preserve being both ..! What was he thinking? And what about his wife and the young kids? He must be mad!

The ‘Rockwell-esque’ picture of the rural New Zealand that we can now only dream of is a gritty introduction to a complex life. Ian paints a picture of a man in a vortex as he tries to tame the beast of the creative soul. Then we’re with him on the road, hitching in winter from one despair to the next, sleeping rough under bushes just out of Levin, midnight flits on unpaid rent… And billowing Wellington wallpaper.

Ian writes with a brutally-astute honesty and doesn’t seem to be holding back on beating himself up… brown and white and the state of thinking from a small colonial country… I like this stuff, it reads like a book, it reads like a living history, our history, our people, our mate telling it from the heart.

Pg 66: “‘Just play yourself.’ I realise I don’t know who myself is. I play somebody else playing himself.” This is the Mune we know and love. We never knew ’til now that he knew what we always did.

It seems that a few of us have been in the inner Mune sanctum forever and continue to ‘bags’ him for the sometimes flawed character he is. He’s that actor-writer-director that could – and we knew it was going to be dangerous, that’s why we hang around – to get closer.

The book is out for Christmas. The first thing you do is go to the back pages (index) and look up your own name; we’re performers and entertainers – our egos got us where we have ended up, not so much a cork on the tide but a determined paddle against the current. This is very much so for Ian more than most.

I was there for some of it (his life so far that is), I was sometimes on the edges of it, and then sometimes closer to the centre than I cared to be. A life? It fits neatly into 328 pages. It doesn’t meander – and neither does the Mune. The preface has an apology to those missing in action and the details cut to the floor due to lack of space – but even so we get enough of this very busy life. His life. I could have done with more.

We’re all in it, in the sense that its about being a ‘Kiwi’ bloke. It starts on the stage as that kid that got a reaction, that first addictive moment when they laughed; they laughed with the actor because of the action and because of the timing… All this was to do with a prop (a pea) that did what it was supposed to (or was it a fluke?) – but, as they say, “the rest is history.”

Ian Mune, one of the original old hands: a guy who started when there wasn’t a professional Theatre and the Film Business was trying to re-invent itself. Both had to be built nearly from scratch – dreams and hard work and sacrifice. You could call him a Pioneer, a Legend, or – as the trades now refer to those from that era – Veterans. John O’Shea always used to stutter, “Mmmmmmaaaakes me sound like a ffffuuuucking old car when they call me that.”

It goes from there to here and back: Wales and the World, more rough and tumble, theatre in the extreme, celebration and disappointments, a family displaced over 4 months of travel and young kids who don’t recognise their Father, a family trying to find itself again… This is a ripping yarn, a page turner. I like this stuff.

In the epilogue he refers to “a friend gone feral” – a mutual friend to be exact. It’s probably the constant burden of those damn mental health issues that have created this rift. No one’s to blame, no one’s at fault – I’ve intervened twice now and put the pieces back together… There’s still hope. This book might just do the trick. It’s a great read.

_______________________________

This review was first published in the Screen Directors Guild of New Zealand’s TAKE magazine, free to members and for sale at: Unity Books, Wellington; Mercury Subs; iSubscribe; Aro Video, Wellington.

_______________________________

For more details on the book, click on the title above. Go to Home page to see other Reviews, recent Comments and Forum postings (under Chat Back), and News.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Multi-levelled story an absolute treasure

Review by John Smythe 18th Dec 2010

I have a fantasy that MUNE an autobiography will be read by all Creative New Zealand and NZ Film Commission board members, CEOs and key staff members over their Christmas break, not just because it raises some key questions about the institutions they work for, but because it will reconnect them with “the clear, passionate voice of the New Zealand artist.” (p.296)

We get family – grandson /son /nephew, husband, father, grandfather; life and work in rural, urban and international settings; the pursuit of acting, writing and directing in live theatre, television drama and feature films – something of a ‘Renaissance man’ himself, he participates in the renaissance through all three domains. And teaching. Mune is a born teacher, not least because he is always learning and he is compulsively generous with what he discovers.

Reciting a poem about peas and honey in a Tauranga Sunday School concert, aged 5, gives him his taste for engaging an audience; for working the laugh. “It is the laughter of unanticipated recognition, and for the last 60 years that is where I have hung my hat.” (p.9)

Being a scriptwriter, he shares his experiences in the present tense, giving them fresh vitality as he confronts, critiques and sometimes allows himself to celebrate the boy /youth /man on his never-ending quest for authenticity in himself, his work, his life and the world around him. By including his own flaws, downfalls and redemptions in the mix – knowing, I’m sure, that this is the key to a central character we can relate to – he earns the right to assess, in retrospect, the systems and organisations he works within, and this too is a gift to us all.

Theatre-wise (which he is), the plot takes him through school and ‘am-dram’ in Tauranga; to Wellington’s Victoria University and Training College then Downstage (where he sets tables, designs posters, paints foyer murals and helps build sets as well as acts), the New Zealand Theatre Centre (which rose from the ashes of the New Zealand Players) and NZBC Radio Drama; the Welsh Theatre Company (where Keith Johnstone, the father of Theatre Sports, was a crucial influence); back to Downstage with Dickie Johnstone (no relation), this time to direct, then on to Auckland’s Mercury Theatre …

Screen-wise (that too) he acts in early TV drama (Pukemanu, Hunters Gold) then hooks up with Roger Donaldson to pursue their mutual passion for film, starting small (Derek, Winners & Losers) before making it big with Sleeping Dogs, for which their reward is to get no backing from the newly-formed NZ Film Commission for their next one: “Nobody doubts you can do it. It’s just … well, there was a feeling that you’ve had your turn.” (p.206) It is at the Cannes Film Festival, hustling, that Mune discovers what drives his passion:

If you presented their lives as a plot for a novel, an assessor /publisher /editor would cry, “Too much and it’s all over the place!” But real life tends to be like that, especially for those trying to make a living in theatre, film and television – or live with such a person – in a small country like New Zealand. Being multi-skilled, self-employed and able to create your own projects, as well as work to order for others, is a fundamental requirement of survival, and the Munes embody the struggle, stress and joy of all that.

One of Ian Mune’s many skills as a writer is the ability to distil a play, film or miniseries to its essence for us, not to mention such phenomena as the 1981 Springbok tour and the forces driving economic boom /bust cycles. He is also very adept at planting seeds for the future fruiting of key ‘plot points’, and stitching recurring themes into the rich tapestry of an extraordinary life that speaks of, to and for us all.

Given the book’s great values, it may seem petty to note the odd error and stylistic slip, but most should have been picked up in editing, so I will.

Having mentioned a Downstage production of Genet’s The Maids and told us artist Pat Hanly “is going to design the set for the upcoming Beckett’s Happy Days” (p.94), Mune goes on to tell us he is “building Pat Hanly’s Maids set, an irregularly shaped mound of sand in which Pat Evison will sit up to her waist …” (p.95). That, of course, can only have been for Happy Days.

An anti-establishment student called Derek arrives on page 60 and threads his anarchic presence through the next 100 pages before he is identified as Derek Morton. This could be a legitimate device but the index has only the one entry for him: p.160. In a sequence about Don Selwyn, Mune mentions “a Moynihan episode” out of the blue and it’s not until five pages later (p.196) that we learn Moynihan is a new TV series (in which Mune plays the lead).

Film historian Leslie Halliwell is misspelt as Helliwell (p.181), and Frank Finlay (brought over to play Justice Mahon in Erebus – The Aftermath) is credited as having played “in the British TV series Bouquets and Barbed Wire” (p.266) when it was Bouquet of Barbed Wire.

These quibbles aside, the book is beautifully designed with a liberal sprinkling of photos and a comprehensive index that renders it highly usable by the many students of theatre and film who will undoubtedly use it in their studies. There are also shaded panels of text that detail ‘The Actor’s Nightmare’ (p.99), ‘The English Theatre’ (p.110), a summary of media and public response to a small Welsh mining town disaster (p.114), ‘Who Are All Those People Standing Around On A Movie Set?’ (pp.161-163), ‘Sleeping Dogs – Synopsis’ (p.191) and two contrasting imdb.com reviews for his film adaptation of Bruce Mason’s The End of the Golden Weather (p.283).

Every part is told with a sense of purpose, not the least of which is the contribution it makes to us. The oft-repeated actors’ mantra, “Where have you come from, what do you want and how are you going to get it?” brings an underlying cohesion to this story, which – like an epic film – constantly changes direction, as internal flaws and external forces conspire to render it unpredictable.

His stories about the different ways he approaches roles as an actor, and works with actors as a director, engage us as co-questers rather than as passive students of his wisdom. When faced with the challenge of playing real people on screen: Morrie Davis (Erebus – The Aftermath), Rob Muldoon (Fallout) and Winston Churchill (Ike: Countdown to D-Day), his quest for truth in performance reaches well beyond imitation.

The odd experience of the conventions of English theatre and Hollywood – “Lalaland” – only confirm his fundamental desire to stay in NZ and tell our stories. But that is not easily done. In 2000, on receiving the Rudall Hayward Lifetime Achievement Award, Mune uses his acceptance speech to confront the NZ Film Commission with what it has become, reminding them it had been formed “with a clear brief to support this burgeoning new industry.” While he acknowledges – in the book – the “invaluable support” he has received at times from the NZFC, and Creative New Zealand too, he feels the industry is in a state of confusion:

Given he was the first person to bring Keith Johnstone-style improvisation to NZ, in the summer of 1968-69, and employed those interactive co-responsive principles in much of his subsequent work as an actor, director and teacher, a project called Birth, Death and the Bits Between – a comedy of bad manners, may well be the best Kiwi film we will never see.

A collaboration between Mune, screen acting coaches Vicky Yiannoutos and Michael Saccente, and an eclectic group of extremely talented actors, its devised story is interwoven from various pairings and groupings. (Think Robert Altman, perhaps?) But the NZFC refuses production funding because the script they are obliged to turn it into “doesn’t cut it.” Mune goes into meltdown and a gaping hole is left in our screens, except for the odd acting role he snaps up.

Mune’s book ends with cogent observations on the state of our television, “wiggling and very noisy wallpaper”; theatre, “… kids are putting plays together, writing, producing, performing all over the place. And they’re good!”; film, “A lot of actors and crews are working for mates’ rates or nothing on Kiwi movies and trying to make a living out of American stuff” … and Peter Jackson’s report on the NZFC:

There are so many levels on which MUNE an autobiography is an absolute treasure. As well as being a ‘must read’ for all actors, directors, producers, designers, crews, funders, administrators and supporters of NZ theatre, television and film, it is an absorbing story of a creative New Zealand life well lived.

_______________________________

For more production details, click on the title above. Go to Home page to see other Reviews, recent Comments and Forum postings (under Chat Back), and News.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

John Smythe December 28th, 2010

Thanks Ian -

I had intended to farm the book out because I really didn’t have time to sit down and read it, let alone review it, before Christmas. But I made the mistake of dipping into it – and was hooked. I’m only sorry I didn’t get the job done faster. Given I think it should appeal to most visitors to this site, I’m hoping many got book tokens for Christmas (or exchange cards with books they didn’t want).

I offered to trim down the above review for The Listener but the Arts editor told me one has already been written and he is just waiting to run it. Hopefully the same is true of other publications.

Ian Mune December 28th, 2010

Hello John,

John Smythe December 18th, 2010

Fixed now - and thank you, Brian, for emailing the corrections. Given this site is also a long term archive, it is never too late to get something right.

Brian Sullivan December 18th, 2010

Thanks for the great review, I have the book on my list of presents for under the tree. One comment John you talk about Ian's edits see your own minor errors. People who live in..

All fixed now, sorry about being a pedant.

Kind regards

Brian S.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments