Othello

12/05/2007 - 09/06/2007

Production Details

By William Shakespeare

Directed by Jonathon Hendry

The greatest account of sexual jealousy in any language, Othello is one of Shakespeare’s most popular and poignant tragedies.

At the heart of the play lies the simple love story of the heroic General, Othello, and his beloved young bride, Desdemona, two people defying society in order to follow their own hearts. But their love is corrupted by Othello’s own destructive weakness and ill-placed trust in the villain Iago, resulting in his growing suspicion in Desdemona’s fidelity. An intense, domestic tragedy unfolds.

Written over 400 years ago, Othello still has the power to shock and impress. The issues of race, power, war and sexual jealousy still resonate in society today.

“O, beware, my lord, of jealousy! It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock the meat it feeds on.” – Iago, Act III, Sc. 3

Director Jonathon Hendry’s striking elemental vision for this production draws from our own turbulent colonial history. Set in New Zealand during the musket wars, Othello is Māori born and missionary-adopted. Now a powerful General of the British Army he arrives back in Aotearoa a stranger in his own land. As the tragic events unfold Othello’s rigid control slips away and the trappings of society, status and order crumble to reveal a broken desperate man.

“Reputation, reputation, reputation! Oh, I have lost my reputation! I have lost the immortal part of myself, and what remains is bestial.” – Cassio, Act II Scene 3

With an inspirational creative team, we bring you theatre in the round at Downstage once again. You will be taken to 1840s Russell, where merchants came to trade in any currency possible, where no laws were enforced and where New Zealand started to form as a nation.

Jim Moriarty as our Māori Othello is excited at the prospect of another bite at this challenging role after performing in the Court Theatre’s acclaimed season in 2002. A celebrated NZ actor and director, who has performed in over 100 professional theatre productions throughout New Zealand and also in Australia, America, Britain, Scotland, Greece and Europe. Highlights include Michael James Manaia, Te Hokinga Mai, Purapurawhetu and directing Once Were Warriors – The Musical.

‘Moriarty burns up the stage as a fiery Māori Othello, enjoy this vibrant, dynamic and inventive production.’ The Listener

Jim’s the driving force behind the youth performance programme Te Rakau Hua O Te Wao. Te Rakau is a brilliant programme which helps troubled youths take ownership for the consequences of their actions and understand how the past impacts on the present during a process of devising drama and kapa haka – predominantly touring performances around prisons and schools.

“Excellent wretch. Perdition catch my soul, but I do love thee and when I love thee not chaos comes again” – Othello Act III Scene 3

Passionate director Jonathon Hendry comes to this project after three years as Head of Acting at Unitec. In 2005 he mounted a sell out revival of The Boys in the Band for Silo Theatre, which toured to Downstage in 2006. In 2004 he directed Elena’s Cultural Symphony at the MFC, which travelled to the Shanghai International Arts Festival in October 2006.

Performance Times

Monday – Thursday 6.30pm

Friday & Saturday 7.30pm

Matinees Sat 26 May, 2, 9 June 2pm

FREE Post Show Talkback

Monday 14 May

$20 Shows

Fri 11 May

Tue 15 May

Tickets

Premium $39

Premium concession/groups 8+ $30

Members $29

Students $28/$18 2hr standby

School parties $10 each

Children under 12 yrs $10 each

Cast

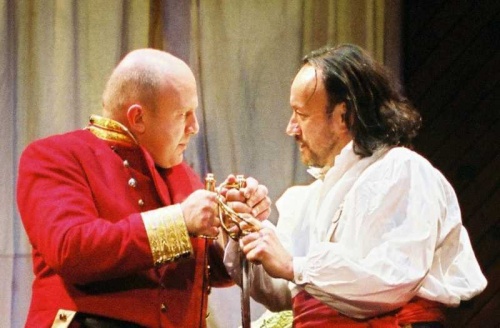

Jim Moriarty . . . . . . .Othello

Peter Hambleton . . . Iago

Madeleine Hyland . . Desdemona

Jennifer Ludlam . . . .Emelia

Steven Ray . . . . . . . . Brabantio/Gratiano

Simon Vincent . . . . . Cassio

Paul McLaughlin . . . Duke

Alistair Browning . . .Montano

Julian Wilson . . . . . .Roderigo

Kali Kopae . . . . . . . . Kali Kopae

Laurel Devenie . . . . .Company

Sam Downes . . . . . . .Company

Ryan Richards . . . . . Company

Sophie Hambleton . .Company

Ed Clendon . . . . . . . .Company

Designers

Set - Brian King

Lighting - Jennifer Lal

Costumes - Lesley Burkes-Harding

Sound - Kane Parsons

Production List

Costume Assistant - Sheila Horton

Fight Master - Tony Wolf

Fight Captain - Allan Henry

Māori Adviser - Mihaere Kirby

Moko - Frankie Karena

Production Manager - Ross Joblin

Stage Manager - Sarah Pearce

Technical Operator - Marc Edwards

Set Construction - John Hodgkins, Iain Cooper

Publicity - Brianne Kerr Publicity

Production Photography - Stephen A'Court

Theatre ,

3 hours 5 mins, incl. interval

Vague, confusing, distracting, and culturally risky

Review by Ewan Kingston 21st May 2007

At the climax of Shakespeare’s Othello, the Moor muses aloud on his plan to kill Desdemona. He kisses her while she sleeps, ceases, then utters "one more, one more" before kissing her again. When some of the school students watching Jonathon Hendry’s production at Downstage saw that action, they chuckled, rather than wept. I had sympathy for them. I was not emotionally hooked by this play. All night my attention had periodically wriggled free of the action on stage. It was no wonder Othello’s struggle between devotion and rage didn’t hit us where it hurt.

What went wrong? For a start, the New Zealand setting. The time of the piece was left (deliberately?) vague, and the details of geography – Sydney working as Venice, Cyprus becoming Kororareka/Russell – were also only supplied to those who chose to buy a programme and read not the directors, but the Set Designer’s note. Instead of making the play more ‘evocative’ this ambiguity meant we were constantly scanning the performance for non-existent clues about the exact time and place of the action.

Even if we had been explicitly told the time and place, 1840’s Kororareka would still have been a poor choice. Why … [Read more]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

A problematic play

Review by Lynn Freeman 17th May 2007

Setting the tragic story of a jealous Moor in patronisingly racist colonial New Zealand is a stroke of genius, and Cathy Downes’ production at the Court Theatre worked like crazy. The same concept is employed in the Downstage production, this time directed by Jonathon Henry and starring the same Othello, Jim Moriarty (seen far too rarely on our stages now). It’s no carbon copy, Hendry has his own style and the setting is not obviously New Zealand – place names aren’t changed, but we hear fantails and a morepork amidst talk of Venice and Cyprus.

The first hour is far too static – long monologues, little movement to break them up, and it drags. There’s a problem too with the chemistry between Othello and Desdemona (Madeline Hyland) – there is none until the much more dramatic second half. That comes almost too late for us to believe Othello would do what he does crazed with passion that been poisoned through jealousy. I say almost, because the bed scene is genuinely impassioned on both sides, fuelled by Jennifer Ludlam’s riveting outburst as the Iago’s exploited wife.

Iago, the ultimate villain, is played by one of the nice guys of the stage, Peter Hambleton. You quickly push aside his past cuddly roles – this is evil personified. Hambleton never takes his eyes of Othello, his enemy. Both men so very alike – destroyed by jealousy to the point where they are prepared to murder. It’s chilling.

The second half scenes with Hambleton and Moriarty are terrific, as is the one where Iago’s sudden cruelty to his wife is genuinely shocking. Moriarty warms up to his part by the second half he’s seething with passion as his British reserve is stripped away and he becomes what those around him believe him to be – savage and wild.

Brian King’s in-the-round set isn’t at all suggestive of New Zealand, (deliberately, he tells us in the programme). A large rock is set in (whiffy and muddy) peat which is variously a beach, water, land, a bedroom and so on. He does though provide the huge cast with many exits and entrances, which Hendry uses to full effect.

There are a few problems with the production but it’s a problematic play.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Could be more gripping

Review by John Smythe 15th May 2007

There is nothing majestic about the tragedy of Othello. It is a turgid tale of wanton destruction that demonstrates how petty jealousy can corrode romantic passion to the point that it turns to homicidal hatred, taking innocent lives in the process.

Unlike Hamlet, Macbeth and King Lear it involves no quest for a throne, vast tracts of land or regal powers. It involves no kings, queens nor courtly settings; it is mostly set in a barracks town and largely involves jobbing soldiers. Othello is a domestic and neighbourhood tragedy and this is what distinguishes it.

It pitches its themes of love and loyalty versus jealousy at a level to which we can all relate. It can speak very directly to us all about our own lives and demand we question our own inner thoughts, feelings, passions and desires, and the actions – or inaction – they may provoke.

Conceptually, this Downstage production owes much to the memorable 2001 Court Theatre one, directed by Catherine Downes (then Artistic Director of Court Theatre, now Director of Downstage), which also featured Jim Moriarty as Othello and Jennifer Ludlam as Emilia. Whereas that was set in the Waikato during the 1860s land wars, this one – directed by Jonathon Hendry – is apparently set in Kororareka (aka Russell) in the 1840s. Unlike the comprehensive Court programme, the Downstage programme says little about the historical context[i] but I assume it takes place around the time Hone Heke was felling flagpoles and he and Kawiti attacked Kororareka. So Venice, Cyprus and the Turks stand as metaphors for Auckland, ‘Russell’ and the disaffected Māori respectively.

In both cases this Othello was Māori born, adopted by missionaries and taken to Britain to be educated. Now he returns as a British Army General, a stranger in his own land, dispossessed of his true culture and with a tenuous grip on his adopted one. "The Moor", then, equates to "the Māori" when specifically applied to Othello. It is a premise that strongly supports his need to give and receive love and loyalty, to feel he belongs and that someone belongs to him. Psychologically it also underpins his extreme reaction when finally convinced he has been betrayed.

Moriarty begins impeccably groomed with military bearing and a crisp English accent then, as "the green-ey’d monster which doth mock the meat it feeds on" gnaws at his guts, some deep-set race memory of aggressive/defensive warrior posturing permeates his physical being and the trappings of cultivated class-conscious propriety fall away. It is the move from controlled to uncontrolled passion that gives this performance shape and meaning. If anything, more could be done to convince us Othello is losing touch with his rational mind as the "monster" invades it.

Madeleine Hyland gives us a thoroughly strong-willed, if naively passionate Desdemona. Her power to turn her senator (read governor’s official) father, Brabantio (Steven Ray) from appalled opposition to her coupling with Othello to duty-bound acceptance of their marriage lays a firm foundation for her determination to plead the cause of the wronged Cassio, which is what gets her into such lethal trouble thanks to Iago’s distortions. The question of her honesty is nicely shaded by her ability to "beguile the thing I am by seeming otherwise" when she fears Othello may be lost at sea.

At the other end of the social spectrum, and just as essential to this small male-heavy community, is the courtesan. As well as giving us a feisty, independent Bianca, Kali Kopae brings more Māoritanga to the action. It’s not her fault that in his enthusiasm to give the tanagata whenua a place to stand in this story, Hendry has her give Othello – who has no tribal affiliations – a rousing Māori welcome on his return from defeating the ‘Turks’ (i.e the Māori ‘rebels’.)

The offstage haka when the "monster" stirs within Othello is more valid. And given this resurgence of his cultural identity, the final haka, performed almost subliminally behind the audience and featuring the word "kupapa" (the name for Māori friendly to the Crown), adds cultural resonance to the dramatic conclusion. But I digress …

Simon Vincent takes Cassio through a convincing range of states of being the loyal professional soldier, devastated loser of his reputation, admirer of Desdemona’s great qualities as his advocate, treater of Bianca, his ‘mistress’, as an object, and cheap drunk too easily provoked to violence.

The other abject pawn in the game is the gulled Roderigo, played by Julian Wilson as a wealthy but lonely landowner in desperately unrequited love with Desdemona. Once reduced to a pathetic whiner, stripped of his wealth by the devious Iago, it is clearly untenable to Iago that he of all people should expose him for the duplicitous, conniving villain he is (see below).

Also top-hatted and frock-coated are Steven Ray’s Brabantio and his brother Gratiano, and Paul McLaughlin’s Duke (conflated with the nobleman Lodovico to suggest the colony’s governor – FitzRoy if we want to be literal). Alastair Browning’s Montano wears a kilt, however, and comes over as very hands-on in securing the colony against disorder.

Sitting between the other two women on the social scale is Iago’s wife and Desdemona’s maid, Emilia. Dressed pragmatically to reinforce the sense of an early settler struggle, Jennifer Ludlam emphasises her character’s tired cynicism, counterpointed by an almost latent need for the approval of her emotionally abusive husband. Given her complete lack of sensuality, Iago’s fear that both Othello and Cassio have bedded her comes over as either an irrational rationalisation to help justify his actions or rampant paranoia.

And so to Iago. Bitter, in the first scene, at being consigned to the rank of Othello’s ensign while Cassio is elevated to lieutenant, it is Iago who largely drives and manipulates the unfolding plot. Thus the choices made about what drives him, and why he takes revenge the way he does, lie at the core of any production. Is he a closet manic-depressive with the surface skills of a diplomat, a diabolical sociopath[ii] incapable of human empathy, or a small-minded man who gets himself and others into big trouble because his desire for revenge gets him onto an increasingly exciting ride he can’t get off?

I have always favoured the latter, with excursions into both other states (we are all capable of behaviours that verge on manic-depressive and sociopathic, given sufficient cause), because that is what makes the play most accessible, interesting, dramatic and meaningful: there, but for the grace of whatever feeds our conscience, go we. And this seems to be the line Hambleton and Hendry have taken too.

Hambleton’s Iago – more middle-aged than Shakespeare envisaged ("four times seven years" = 28) – is an average soldier with delusions of grandeur who fears life is passing him by. His bitterness is recognisable and so is the glee with which he gets his revenge. Up to a point. If we accept the proposition that it all escalates beyond what he has intended – which is presumably the discrediting and demotion of Cassio and his own elevation in his place – the focus must be clear on the key turning points that escalate the plot and take him places he has never been to before.

One such turning point is when Roderigo threatens to expose "honest Iago" (see above). Given his efforts to manipulate Roderigo into killing Cassio, after Othello asks Iago to see it done, I take it that Iago is unlikely to have killed a man before, least of all one of his own battalion, and it is not something he relishes. Until he does. Then there is no stopping him. "This is the night that either makes me or foredoes me quite" is surely the cry of a man experiencing this level of risk for the first time.

Hambleton brings great clarity and intelligence to his reading of Iago as one who presents as loyal and dependable while being anything but in private. But I find myself craving greater insight into his growing panic and inner excitement as he keeps on surprising himself at his extraordinary talent for manipulating other people to exact revenge then cover his tracks while preserving his "honest Iago" reputation. At the end, however, once brought to his knees, we do see that he has the human sensibility to look traumatised at the carnage his jealousies have wrought.

The supporting actors – notably Laurel Devinie playing the ‘Clown’ role as a no-nonsense housekeeper – do an excellent job of filling out and moving on the action.

In Brian King’s boardwalk and dirt pit setting, furnished only with one large rock and a jutting ramp covered with woven webbing – destined to become the bed where Desdemona meets her doom – the in-the-round configuration works well (from where I sat, anyway). By ‘casting’ the audience early as a suddenly assembled Senate, we remain well positioned to observe the action and consider the evidence before us with a sense of personal and collective responsibility.

Jennifer Lal’s lighting is necessarily shafted and pooled to catch the action without illuminating the audience. While there is no naturalistic logic as to the source or tone of the lighting, it does produce interesting light and shade textures.

I am not enamoured of Kane Parson’s lapping tide and tweeting birds sound scape, even if that is what Hendry heard as he read the play aloud by candle light in the Bay of Islands (see endnote #i below). The storm effects are good but – given the use of kapa haka elements to suggest inner turmoil – I’d have thought volcanic and seismic rumblings might have been better employed.

Lesley Burkes-Harding’s costume designs evoke the era well without being over-pedantic. However one detail does trouble me. There is no difference between the uniforms of Lieutenant Cassio and Ensign Iago, and given Cassio is stripped of his rank by having an epaulet ripped from his shoulder, there should be.

Over all, although not yet as gripping at it may become (I saw the Friday night preview and the Monday night performance), this Othello is clear, relevant and very accessible, as evidenced by the enthusiastic response of a large crowd of high school students from Tawa. Strong images abide and that is always a good sign.

[i] I have scoured the programme for clarification of the conceptual rationale. Hendry’s programme note includes, "My latest return to Othello began at Te Whahapu near Russell as I sat on the deck of an old soldier’s cottage (reputed to have been New Zealand’s first brothel) listening to the sound of the water lap and the bird cries as I read the play aloud by candle light. The environment and its history felt the place to begin to build our world of the play."

The Designers’ Notes include, "The costuming for Othello has been based upon that of the late 1840s, as might have been worn by people in Kororareka, just before the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi" (my emphases) – which any school child will tell you was signed in 1840.

The media release includes, "Set in New Zealand during the musket wars, Othello is Māori born and missionary-adopted. Now a powerful General of the British Army he arrives back in Aotearoa a stranger in his own land … You will be taken to 1840s Russell, where merchants came to trade in any currency possible, where no laws were enforced and where New Zealand started to form as a nation." Given the Musket Wars were in the 1820s, and inter-tribal, this must mean Othello was taken from that environment to return in the 1840s – which would put him in his mid-20s, but that’s too pedantic. It’s not a literal transposition.

[ii] Given many dictionaries do not include ‘sociopath’ (even though it was coined in 1930), I offer this definition from dictionary.com: "a person, as a psychopathic personality, whose behaviour is antisocial and who lacks a sense of moral responsibility or social conscience."

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

martyn roberts May 15th, 2007

er you do mean the musket wars were in the 1820's to 1835 don't you John? Yes indeed - thanks Martyn - duly corrected. JSMake a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Stimulating Othello with a Kiwi setting

Review by Laurie Atkinson [Reproduced with permission of Fairfax Media] 15th May 2007

Jim Moriarty, following the late Don Selwyn and George Henare, is the third Mâori actor to play Othello at Downstage since the theatre was founded in 1964, but he is the first to play the role in a production that sets the play in New Zealand during the land wars.

In Jonathon Hendry’s imaginatively staged in-the-round production, the colonial atmosphere is created through costumes, sound effects (bird song in the bush, some of it irritatingly scratchy), and a strong sense of the Victorian social hierarchy.

One soon ignores the references to Cyprus and the Turks as Simon Vincent brings to mind an honest, straightforward Dickensian hero such as Pip in Great Expectations with his excellent Cassio and Madeleine Hyland, who looks as if she could have stepped out of a Thackeray novel, creates a touching Desdemona whose careful upbringing has not prepared her for the passions aroused in her by Othello.

Moriarty’s Othello is a Mâori who has been absorbed into the British army and is clearly a charismatic military leader commanding respect. He doesn’t speak down to or joke with the senators when he explains how he wooed Desdemona, he simply tells an unvarnished tale.

But when Iago’s poison begins to work on him and he casts off his Pakeha ‘skin’ he reverts, with an unnecessary off-stage Mâori chant to underline the point and making it hard to hear the words, to his traditional "marble heaven."

However, the Victorian milieu somehow seems to have suppressed the volcanic emotional eruptions that occur in the final scenes of the play. The terrifying "I will chop her into messes. Cuckold me!" is down played and not in the almost operatic tone that it seems to demand, and the same applies to the amazing "Whip me, ye devils" speech which is again drowned out by, this time, an unnecessary on-stage Mâori chant.

Peter Hambleton’s Iago does not have the cerebral viciousness usually associated with the role but he brings out the cruel humour and the furious passion of self-regard that this double-dealer has. He leads Julian Wilson’s funny, wimpish, and appealing Roderigo by the nose as he filches all his money and his self-respect with sang-froid, and he treats Jennifer Ludlam’s fine, down-to-earth Emilia with disdain and violence. This Iago’s ‘honesty’ is believable.

At the centre of Brian King’s austere setting, around which are banks of seating for the audience, is a large sand-pit surrounded by platforms that hint at wharves and wooden structures of the young colony. Downstage’s balcony is also used as are the steps rising to the back of the auditorium. All this is most effectively exploited in the fights and the torch-lit attack by Roderigo on Cassio is marvelously murky and exciting.

The intimacy of actor to audience is used well in this the most domestic of all Shakespeare’s tragedies with Othello making us all senators near the beginning and Iago taking us into his confidence with his evil thoughts. There’s a price to pay: the occasional lost word or speech depending upon where you are sitting. But overall it is a stimulating introduction to the play.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments