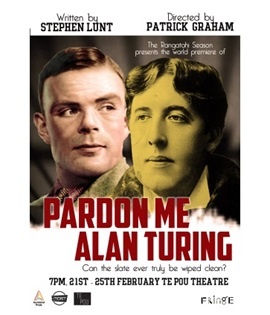

PARDON ME ALAN TURING

Te Pou Theatre, 44a Portage Road, New Lynn, Auckland

21/02/2017 - 25/02/2017

BATS Theatre, The Heyday Dome, 1 Kent Tce, Wellington

01/03/2018 - 04/03/2018

NZ Fringe Festival 2018 [reviewing supported by WCC]

Production Details

Written by Stephen Lunt

Directed by Patrick Graham

Dare You Theatre

On the 6th July in New Zealand and 31st January 2017 in the UK, gay men were posthumously pardoned under a new law, but is it that easy? Is this what these men deserve?

An eccentric Alan Turing, flamboyant Oscar Wilde and their modern day prince, meet across the centuries to ask those very questions. They are joined by a host of other colourful characters in this roller-coaster political comedy with bite. The real question to be asked though, can the slate ever be truly wiped clean?

Auckland Fringe 2017

Te Pou Theatre

21-25 February 2017

NZ Fringe 2018

“If you want hard-hitting drama and to get into a serious discussion about LGBTI rights in both the past and present, watch PARDON ME ALAN TURING.” “The play is a must-see” – GayNZ.com

Reviews: broadwayworld.com

BATS Theatre The Heyday Dome

1 – 4 March at 9pm

The Heyday Dome*

PRICE: Full Price $22 | Concession Price $16 | Fringe Addict Cardholder $15

BOOK TICKETS

Accessibility

*Access to The Heyday Dome is via stairs, so please contact the BATS Box Office at least 24 hours in advance if you have accessibility requirements so that appropriate arrangements can be made. Read more about accessibility at BATS.

CAST: David Capstick, (Jacqui Whall, Andrew Parke, Joseph Wycoff, Geoff Allen

The Creative Team

Pardon Me Alan Turing is Dare You Theatre's inaugural production. It is featuring in the Auckland and Wellington Pride Festivals and the New Zealand Fringe Festival. A development season was positively received at the Auckland Pride, Fringe and the Rangatahi Festivals at Te Pou Theatre in 2017, Directed by Patrick Graham. Its founder, Producer and Writer, Stephen Lunt, is also an experienced producer for Fringe and other mediums.

Theatre , LGBTQIA+ ,

1 hr 20 mins

Offers an absorbing perspective on a shameful past and perplexing present

Review by John Smythe 02nd Mar 2018

Given the gestation time usually required for developing new work, let alone getting it into production, it is a special thrill to see a fully-formed play that responds to very recent history, albeit drawing from a deeply fraught past.

On 31 January 2017, the UK government finally enacted the so-called Alan Turing Law which pardoned, in many cases posthumously, about 49,000 gay men for decades-old sexual offences that were no longer be crimes under current law. Less than a month later, Dare You Theatre mounted a development season of Stephen Lunt’s Pardon Me Alan Turing at Te Pou, in the 2017 Auckland Fringe.

In New Zealand the first reading of an equivalent bill didn’t get to first reading stage until 6 July last year, although Justice Minister Amy Adams did take the opportunity to issue an apology to New Zealand men who were convicted in the past for consensual homosexual activity. There is no record of how many people that covered as the 120 year-old anti-sodomy law made no distinction between consensual and non-consensual acts. Therefore those still living (or their descendants?) are obliged to apply for their conviction to be quashed and many still feel too shamed to step up.

Now Dare You brings Pardon Me Alan Turing, directed by Patrick Graham, to the NZ Fringe at BATS Heyday Dome, to traverse the history of gay repression and ask of the Pardons: “Is it that easy? Can the slate ever truly be wiped clean?”

A cellphone shows us the opening scene is contemporary: two men who found each other on Grindr are on their second date. Daniel (David Capstick) is older, a celebrity columnist and married to his editor, Rachel (Jacqui Whall), whom we have yet to meet. Ben (Andrew Parker) has been disowned by his parents since he came out, recently, and is engaged in a study project about the men who suffered for what they are now free to enjoy; a project that will draw Daniel in …

It’s a seamless segue into the sentencings – pronounced in role by Ben and Daniel – of Alan Turing (Joseph Wycoff) for Gross Indecency and Oscar Wilde (Geoff Allen) for Sodomy (57 years part). Thus the play fluidly blends gay male experiences from three centuries and allows the protagonists to converse with each other.

The different ways the courts deal with Turing and Wilde speaks not so much to a softening of attitudes as to the value the establishment places on Turing’s work compared with Wilde’s. The relative ‘merits’ of incarceration (Wilde) versus probation and chemical castration (Turing) are left to us to ponder.

Those not instantly familiar with these famous names are drip-fed with hints as to their vocations (without explicitly revealing that Turing’s cracking of the Enigma Code was instrumental in Britain winning WWII, or that Wilde was an acclaimed writer and brilliant wit). The focus is firmly on the personal experiences of a range of very different men who happen to have being gay in common. Their various relationships with each other, family, friends and the State play out in present action to build insightful testimonies.

Wycoff is compellingly introverted as Alan Turing, tragically willing to suffer the indignities imposed by the court as long as he can continue with his work. His outbursts are reserved for his overbearing mother, Sara (Whall), and rigidly straight brother, John (Parker). His default state of bewilderment is easy to relate to, as we absorb the full import of the unfolding stories.

Apart from the odd impassioned utterance, Geoff Allen’s entirely valid choice to play Wilde as ailing and mostly bored with the panache and flourish expected of him, has the unfortunate effect of his seeming to lose interest before completing many a sentence; we can only wonder if they are good punchlines we miss. He’s not the only one yet to get the pitch of the Dome space (which, when playing to an audience down one long side, is not as intimate as it may seem). Nevertheless the essence of his unjust fate achieves the necessary poignancy.

As Wilde’s wife Constance, mother of their children, Whall effectively articulates the collateral damage visited on families by the punitive law, especially in Victorian times. She also appears in a gentleman’s club scene as a robust man called Frank, I think (not named in the programme).

Parker completes his impressively diverse triumvirate with a bratty Bosie, utterly lacking in empathy and therefore earning none. That I want to slap him (one could in those days) is testament to the authenticity of his portrayal. I’d have liked to see more of his Ben towards the end, given it’s his project that’s being dramatised, but Lunt choses to concentrate on Daniel as the contemporary story plays out.

Capstick’s Daniel is a lively presence as he conducts his investigation (or is he immersing himself in Ben’s research?), contrasting the excitement of his new relationship with Ben with growing disquiet then anger at the inadequacy of the official Pardons. He and Whall, as his wife Rachel, play out the slow reveal of the exact nature of their relationship with integrity and insight, leaving us to grapple with why it might remain necessary to keep such arrangements secret.

With so many threads to tie up, it’s little wonder the play seems to have multiple endings. Or maybe it’s a function of the central issue remaining unresolved, rendering the desired ‘happy ending’ elusive. Meanwhile Pardon Me Alan Turing offers an absorbing perspective on a shameful past and perplexing present.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Reflecting the space that remains between intention and resolution

Review by Leigh Sykes 22nd Feb 2017

“Here in New Zealand, the Ministry of Justice has indicated between 50,000 and 100,000 men have been convicted of homosexual conduct … On the 9th February and the 31st January in the UK, reform for these men wrongly convicted and cautioned was passed.”

This is the message that greets us at the end of the play, and this is one of the reasons that the play is timely and relevant. The Production Note in the programme points out that Alan Turing, computer pioneer and codebreaker, was given a posthumous royal pardon for his 1952 conviction for gross indecency following his arrest after having an affair with a 19-year-old Manchester man, and asks where the pardon for Oscar Wilde and the numerous other men convicted under the same law is.

We are not given the answer to this question, but we are able to become informed about the conversation, thanks to the play’s spotlight on the differences of opinion, behaviour and treatment of homosexuality in three different time periods.

The play starts in the very recent past, where Daniel (David Capstick) and Ben (Andrew Parker) are getting to know one another. This relationship serves as a framing device (setting in motion action towards pardoning Turing and the numerous other men convicted) and as a barometer of how much (or little) has changed since those convictions. The twist is that this modern relationship is not as ‘out and proud’ as one would hope, and so becomes fertile ground for Daniel to support law-student Ben’s campaign to seek pardons for those convicted under now-obsolete laws. Capstick’s Daniel is earnest and staunch in his investigation, and he now becomes an often silent witness as we meet Turing and Wilde.

The structure of the play takes a little time to get used to in these opening sections, as Turing (Joseph Wycoff) and Wilde (Geoff Allen) interact with each other and Daniel, in seeming contradiction of their historical situations. Slowly it becomes clear that these interactions are taking place in an in-between space, a ‘waiting room’ of possibilities where anything can happen. Lighting (designed by Ariana Shipman) helps us to distinguish between different situations and different time periods, as the convention of Daniel the observer/investigator, feverishly making notes, becomes clear.

Wycoff presents Turing as often socially awkward, with a tendency to stutter, which makes him very human and credible. Allen’s Wilde is flamboyant and witty (of course) but also capable of deep despair at the treatment he receives from society. Supporting this trio, and in a number of instances outshining them, are Andrew Parker and Jacqui Whall, who both play a number of different characters. As Wilde’s companion Bosie, Parker manages to steal most of the scenes he is in, with his irrepressible high spirits and refusal to succumb to society’s expectations. As Sara Turing (Alan’s mother) Whall is irredeemably and convincingly dismissive of her son, generating much audience laughter at the cheerfulness of her contempt.

For me, the play really comes into focus and is most effective when it concentrates on each of the three major characters in turn, without any interaction between the groups. Capstick and Whall are lovely as Daniel and Rachel, the married couple whose cheerful (and foul-mouthed) bitching about other people is very real and funny. The Turing family (with Whall as his mother and Parker as his brother) are convincing in their family gripes and quarrels, while Allen, Whall and Parker present Wilde’s difficult relationships with his wife and Bosie with sympathy and credibility.

The strands of the story do knit together in the end, and we are left to consider the wrongs carried out in the name of the law and the lack of redress that still means progress needs to be made. There are some eloquent and affecting sections in the play, and the hard-working duo of Parker and Whall make a virtue and strength of their multiple supporting roles, played in Brechtian style by never leaving the stage and changing character and costume (designed by Jacqui Harrison) in full view of the audience.

The conceit of Turing’s case being a framework for knitting together other stories and as a catalyst for change is an interesting one. At times the interactions between the historical characters work well, and at others I find myself a little lost in the in-between space. Perhaps this is the point, and until we can see clearly enough to truly create a clean slate for these historical injustices, we are all a little lost in between intention and resolution.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments