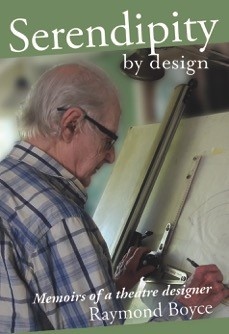

SERENDIPITY by design: Memoirs of a theatre designer

Shakespeare Globe Centre New Zealand, New Zealand wide

27/08/2018 - 22/12/2018

Production Details

An account of an exceptional life, which has influenced so many in the world of theatre design and much more, in his own words.

Raymond Boyce set the benchmark for New Zealand’s theatrical staging in the 1950s and 60s. His career has spanned over 50 years as a stage and costume designer for playhouses, opera and ballet.

Many people, unknowingly, will have been wowed by his scenic interpretations of well-loved productions.

His work is exceptional, and his talent gives visual expression to ideas that are little more than intuition. Classically trained, he designs in a vast range of styles, from baroque to the spare and simple.

Raymond is celebrated for his Globe Hangings designs and his work has established a standard of excellence that all performance-goers have benefitted from.

“My work is only realised in a live performance before an audience of just two and a half hours or so. It has to be flexible enough to reflect audience reaction and the development by the performer … I aim to interpret the intentions of the playwright, composer and the choreographer through the media of director and performers for a contemporary audience.” – Raymond Boyce

RRP $40 incl. GST (general public)

Special Price $35* if collecting the book from the SGCNZ office

Find the order form here.

Raymond Boyce graduated from the Slade School of Fine Arts and the Old Vic Theatre School in the late 1940s and emigrated to New Zealand to join the fledgling New Zealand Players in 1953.

About this time he also started to design for the newly formed opera and ballet companies, and for the Australian Opera Company.

There was little money in theatre design at the time so he and his wife, Geraldine, formed a puppet company and toured New Zealand.

In 1968 Raymond took on the tasks of display designer for Expo ’70 and design consultant to the architects for the Hannah Playhouse. As resident designer at Downstage he produced over 100 plays while continuing to work with Wellington City Opera and New Zealand Ballet.

The Wellington Shakespeare Society commissioned Raymond to design the Globe Theatre Hangings that were presented to the rebuilt London Shakespeare’s Globe in 1994.

Raymond’s guidance and influence is far reaching. He has tutored at New Zealand Theatre Federation schools, Wellington Polytechnic, Victoria University, and Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School. He is Patron of Shakespeare Globe Centre New Zealand.

Raymond is a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) and holds an Honorary Doctorate in Literature from Victoria University of Wellington.

He also received a Governor General Art Award and is a Fellow and Elected Artist of the Academy of Fine Arts.

In 2007 Raymond become one of only 20 living Arts Icons, awarded by the Arts Foundation.

Theatre , Puppetry , Opera , Book , ,

Informative, wise, elegiac, moving

Review by Phillip Mann 27th Aug 2018

On Sunday, May 19th 2018, a goodly number of friends and relatives gathered to celebrate Raymond Boyce’s 90th birthday. Apart from the screening of a short film by Peter Coates in which Raymond is caught on camera discussing his art and the part he has played in the development of New Zealand theatre, this was also the occasion for the launch of his memoir: a work with the enticing title SERENDIPITY, by design.

It is a witty title and one which rewards analysis. Serendipity is the famous word coined by Horace Walpole (c1754); it identifies the faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident. Anyone who works in the arts will know those moments, when new ideas suddenly reveal themselves like a ray of light in a dark room and new possibilities open up. However, in this title, the faculty for happy discovery is immediately qualified by the words, “by design” – in lower case letters, please note. And how important this qualification is, for it reveals the hard work, the careful planning, the burning of midnight oil and the concern for the smallest detail that are the foundation of the most sublime theatrical design.

Thus the title of the book perfectly sums up Raymond Boyce’s gift of a far reaching imagination and superb craftsmanship.

“On a wet summer day in 1951, with a pretty thin folder of designs, I took the long bus ride out of London down to a private girls school in Dulwich which, empty of its girls, was occupied by the Old Vic Theatre … Here I was waiting to be interviewed by Glen Byam Shaw, its director … and Margaret (Percy) Harris, doyenne of theatre designers. I was hoping to gain entry to the training course for theatre designers.”

So begins Raymond Boyce’s memoir.

From his childhood, Raymond’s passion for theatre has shaped his life. Let us recall that before the age of television, the theatre in all its manifestation from music-hall to high-opera and the classics, was the favourite source of popular entertainment. This appetite for drama was catered for by many theatres ranging from the grand and professional to the small and amateur. Theatre was truly the people’s entertainment and well supported by all levels of society.

So, we can imagine the young Raymond, seeing a show, perhaps with his grandmother and grandfather, and then hurrying home, keen to recreate the excitement in miniature, perhaps on the kitchen table or the floor before the fire-place. From a very early age Raymond showed an immense talent as a maker of models and this skill has continued for his entire working life. All directors who have worked with him know the joy of seeing the model of a proposed set design come to life in full colour and with moving parts. We are fortunate that some of these have survived.

Young Raymond made puppets too – another skill which he has retained and practised in his adult life. Even as a child he devised clever ways of changing scenes on his miniature theatres. He also painted backdrops and skilfully created actors from cardboard. These were appropriately costumed and so constructed that he could move them about on the stage.

Whether he ever thought of the future and the possibility of working in the theatre, I do not know, but he probably did in a dreamy kind of way. Creative energy manifests itself early in life.

When he was eleven, the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 led to Raymond, along with many other children, being sent out of London to avoid the Blitz. He describes attending a school at Bedford, which was in those days a quiet rural town some 50 miles away from London. By his own admission, Raymond did not shine as a scholar, but one event stands out in his memory. He was cast as the heroine in the school play, a translation of a French drama called One Does not Jest with Love. This proved to be a seminal experience. He writes:

“I was in seventh heaven: the glory of rehearsals, and then to be ‘made up’, a wig, a costume. I also painted the bits of scenery and props required; this had never happened to me before. I think on the first night (I guess there was only one ‘night’) I transcended into the heaven of drama. I didn’t really know what I was doing, but the audience cheered. I had no idea that it was for me.”

Dud or not at the formal educational requirements of school, Raymond also revealed an enormous talent for sketching and painting. In this, he was following in the steps of his father who was a fine commercial artist, and like many talented people, he seems to have accepted his natural gifts with equanimity. However, Raymond’s passion for theatre continued unabated and came to have a clearer direction.

The war continued and he was billeted in different houses before finally returning home to be with his parents. By 1942 he was back in London and he describes how he and his mother would take cushions to kneel on and peer out of the window and watch the “arrival of the bombers and then the air force fighters, much outnumbered, flying up and trying to shoot them down, which they did, quite often.”

London meant access to theatre which was again coming alive as the war turned in favour of England and its allies. The young scholar was at last able to see great actors such as Olivier, Richardson, Sybil Thorndike and Joyce Redmond perform in Shakespeare, Chekhov and the great Greek dramas. This again fed his desire to work in theatre.

For a while, Raymond thought of becoming an actor himself, but a disastrous audition on the dark RADA stage when he was asked to remove his glasses put an end to that dream. He decided to follow the advice given by his art master, to seek entry to the Slade, the prestigious arts academy. He also decided that he did not want to become a painter: he wanted to be a stage designer.

He applied to the Slade and was accepted. However, before he could begin his training, he was called up to join the army. (Conscription in Britain did not end until 1960.) Raymond’s account of his time in the army is amusing, almost in the Carry On tradition, but the danger was there. He was among those flying to Berlin to deliver necessary food supplies.

Demobbed, he was now free to re-commence his studies. He applied to join the Slade Diploma Course and was accepted. Serious training to be a theatre designer now began … and we have come full circle.

Chapter two, Players and Puppets, describes the early days of his association with New Zealand.

He writes: “At the end of January (1953) I got a letter from Richard (Dick) Campion telling me of his project to establish a national touring drama company, and would I come out to New Zealand to be the resident designer for an eighteen month contract at 12 pounds a week?” He accepted and soon found himself flying out to join the New Zealand Players.

Although the work was varied and exciting, one has the impression that designing for New Zealand Players was not always easy, or satisfying. But there were compensations. New Zealand had no professional drama at the time and this gave him the unique opportunity to “offer to establish a system of theatre design – all my own.” This was when Raymond met and worked with Geraldine (Gerry) Kean who later became his companion when they started a successful Puppet company – and subsequently, his wife.

It was while performing with puppets that Raymond began designing for opera and ballet as well as theatre. An entire chapter, appropriately called Ballet and Opera, is devoted to this work and shows just how complex dramatic art can be. Over the next forty years he was to work on over forty opera productions and direct eleven. He also designed nearly forty ballets. Hence his well-deserved reputation for hard work. We are fortunate that many of his design sketches have survived and are used as illustrations for this book.

In chapter four, appropriately called Drawing the Line, Raymond reveals his working method and some of his secrets. It makes fascinating reading and is the one chapter I think all trainee directors, designers and theatre managers should read. Here we confront the hard work of ‘design’ as mentioned in the title of the book.

He begins, “To start my designing I will read the play four times. The first time will be to read it like a novel, not stopping at stage directions… The next time I read the play it is with care, stopping when I don’t understand and re reading until I do… The next reading will be to understand the ‘traffic’ of the play, where its characters come from and where they go… Then comes a long session where I write down what characters say about each other, what they wear, what social class, what culture, what period, what season and indications of the weather.” Etc.

Well, I leave you to read the rest but this is the most succinct, wise and painstaking description of the dramatic process that I know, and it explains why Raymond is so successful. It is the down to earth design side of the serendipitous dream. The chapter concludes with some advice. In response to the often asked question, “How do I become a theatre designer?” he replies, “From the earliest time, you must know from your very boots that this is the most important life for you. It is a life; it is not a nine to five job.”

How true!

In the next two chapters, Expo and Playhouses, we return to history. I think of these as describing some of the high points in Drama, especially in Wellington. The Hannah Playhouse was built and despite any controversy about its design, it was the home of many magnificent productions, most designed by Raymond.

Toi Whakaari was flourishing. The Drama Department at Victoria University of Wellington was developing new courses. BATS Theatre was thriving. Circa was doing well. It felt like a kind of Golden Age for theatre in Wellington. But that notion took a serious shock when Downstage at the Hannah Playhouse closed its doors for the last time. This loss is still felt.

The final two chapters are entitled Families and Friends and Travelling Hopefully. They have an elegiac quality, for they are chapters of reflection, a looking back after a busy life. I found them very moving, especially the tribute Raymond pays to his wife Gerry whose bright intelligence, hard work and good humour supported him in his work right up to her untimely death in 2002. Mention should also be made of the late Tony Taylor who, with Raymond, created many memorable productions and who, of all the Wellington theatre directors, was closest to Raymond.

So now all that remains is to wish Raymond good health in his retirement, and to express our thanks to Dawn Sanders and Shakespeare Globe Centre NZ for helping to make this book possible.

P.S. – a plea:

When SERENDIPITY by design is re-issued, which I am sure it will be, could a great deal of attention be directed to the index. It is very important, and at present it is very incomplete. I also think the text would benefit from some judicious editing but without destroying the essential ‘voice’, which is Raymond’s.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments