Tempest: Without A Body

ASB Theatre, Aotea Centre, Auckland

05/03/2009 - 05/03/2009

Production Details

NEW ZEALAND PREMIERE

An angel with a broken body, wings crumpled and too small for flight, wanders on the landscape of blood and destruction. MAU, in their dance style of ceremonial ecstasy, emerge from the shadows to pray on the ruins of history.

Through the frozen eyes of Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus and Giorgio Agamben’s Sacred Man, with a message from Algeria and from the small town of Ruatoki, choreographer Lemi Ponifasio has created a poignant, poetic and frighteningly beautiful reflection on the post 9/11 world.

One of the most original and controversial choreographers in the world today, Lemi Ponifasio brings this latest version of his current performance series Tempest, first premiered in Vienna.

"An impressive choreographic tour-de-force." Le Soir, Belgium

A co-production with MAU Forum.

see MAU on YouTube

website: www.mau.co.nz

WHEN: Thu5 Mar 7.30pm

WHERE: ASB Theatre, Aotea Centre, THE EDGE®

tickets:

Premium $55

Premium Festival Friend $45

A Res $45

A Res Friend $40

A Res Concession $40

A Res Group 6+ $40

B Res $35

B Res Concession $30

The textures of terror – should come with a warning?

Review by Celine Sumic 07th Mar 2009

TEMPEST: Without a Body is the third and final instalment in a series of related works by choreographer Lemi Ponifasio. Distantly reflecting elements of Shakespeare’s play of similar name, Ponifasio’s reduced aesthetic and powerful poetic are clearly evident in his concluding episode to the series.

Opening abruptly as house lights are cut and a wall of sound is simultaneously driven into the audience, this is a storm delivered without warning. In what can only be described as a massive acoustic assault, the initial explosion signifying the beginning of TEMPEST: Without a Body is followed by an ominous, industrial sound-scape that effectively sustains the audience in an involuntarily altered state for the duration of Ponifasio’s work.

The theme of terror thus successfully established (understatement), as the sound-scape subsides to something near bearable I notice a figure emerge from the darkness. Feeling the air, he is on high alert as he scopes the floor in a rapid, gliding shuffle, his urgent circling and silent, directional gestures instructive and intense.

A suspended wall, modelled from faceted paper to reflect a surface of rough-faced rock, hangs suspended to one side of the stage.

Advancing in a hesitant traumatised stupor, a soiled and battered angel slowly steps out from her position at the base of the wall. Defeated, her gaze fixed upwards, she presents the angelic altered; the destruction of mediating grace.

Stepping forward to scream her horror upon us, the angelic figure is acknowledged by Ponifasio in the program notes as drawn from Walter Benjamin’s observations of painter Paul Klee’s work Angelus Novus which depicts the angel of history faced with the horrors of the past while being blown hopelessly towards the future.

While not consciously alluded to, Ponifasio’s angelic figure also echoes of Shakespeare’s Ariel, a much utilised figure in post-colonial discourse for which Shakespeare’s The Tempest has gained considerable renown since the 1950s.

Continuing in this vein of revolutionary political action is Ponifasio’s company MAU, which translated means just that (revolution), supported by MAU’s vision of peacefully enacted change by means of artistic endeavour.

As ominous echos continue to unroll as if from within the body of a collapsing Titanic, the swiftly stepping incantations and gestural directives of Ponifasio’s gliding group of prayer-makers enact an urgent call to the sinking vessel we call Western Civilisation.

The contrast created by the light on the suspended wall dances with my eyes, creating a sense of emerging mirage. A densely intelligent use of set, its apparent simplicity belies a wealth of meaning delivered with layered, ambient force.

Giving audience only partial access to figures in motion, light plays upon and around the suspended wall variously creating a frozen vertical river, a massive weight about to fall, an element framing an illuminated interstices and a half crucifix modelled in light in three dimensions.

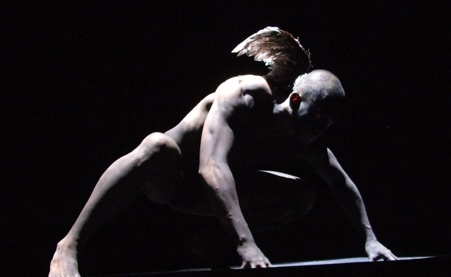

Drawn to this path of light is a figure turning at a butohesque pace. In an incremental revealing his naked back becomes a visceral landscape; the edge condition of Agamben’s bare life. A trio enter, partially obscured by the wall, to roll the bare life figure with their approaching steps of air. He spins away, as if kicked. The partial reveal of the figures behind the suspended wall makes them appear only partially human and partially one with the wall.

Enter the beast, another of Shakespeare’s Tempest figures loosely alluded to in Ponifasio’s work, whose circular path crosses the space with a lilting, light-footed malevolence. With horns of hair and fists as feet, his ambivalent role is revealed as he comes to a stop and shows his face, curling quietly to a collapse amidst the sound-scape of dog barks and industrial echoes.

As the angel reappears to drag the collapsed beast off stage Ahmed Zaoui’s face emerges projected upon the back wall of the theatre.

The sound of dogs barking increases to a vicious loop to mark the appearance of local ‘face of terror’ Tame Iti, who emerges from the gloom to display his spectacular tattoos and throw a challenge to the audience. Iti returns again near the end of the work, this time in a suit, his impassioned call extracting a response from the audience.

Mutual marketing ploy aside, Iti’s figure has considerable presence and his inclusion in this work – along with the image of Zaoui – makes an interesting embrace of contemporary moments in New Zealand history.

TEMPEST: Without A Body makes references both to the choreographer’s Samoan heritage, reflected in the sasa movements of the gliding monk-like figures, as well as to Ponifasio’s butoh background, lending a finely crafted sense of very slow, contained movement to the work.

On a critical note, I have to question the acoustic violence used to open this work. To subject an audience to a traumatic sensory experience without warning presupposes the audience lacks knowledge of terror and that therefore the imposed sensory assault is necessary in order to create the ground on which to build the work. For my part, and my unprepared friend however, this was not the case and we found the result unnecessarily disturbing.

One wonders whether there isn’t a better way to communicate a concern for the issue to terror than to immerse the audience in a direct experience of it. Suffice to say; at the very least this show should come with a warning to those with a heart condition.

Rewinding her path to her original starting position, the angel returns to announce a turning point in the work as her outstretched and bleeding hand reaches towards the suspended wall. The small river of blood running down the angel’s arm is matched simultaneously by projections of a slow spreading red flood across the wall.

Ponifasio is at his best in his reduced and powerfully abstract aesthetic, so it seems out of place at a number of points for the strength of his more monumental approach to be broken by moments of pedestrian theatrical gesture.

Less successful moments occur in the latter part of the work and include the section where the angel rubs her head vigorously in a crouching position after the wall has been conceptually rinsed of blood, and again when a figure breaks a slab of plaster over his head at the end of the work. In my view the scale, nature and speed of these gestures detract from the overall resonance and strength of the work and suggest further crafting is required before this show is fully artistically resolved.

A trio of gliding monks make their final incantations following the slow rinsing of the projected blood from the wall. The light is extinguished as the last of the blood is rinsed away and a large scale image of a kuia’s face emerges from the darkness to the sounds of faint keening.

As the wall is symbolically cast to the ground in baskets of thrown plaster, lasting images for me would have to include the slow motion swimming of a near naked figure, raised on a platform, as if exhibited in a coffin of light. Tame’s call and response from the audience also reverberate in my mind, as this work closes and the various textures of terror are left to settle in the dust.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Turmoil and suffering produce lasting impressions

Review by Nik Smythe 06th Mar 2009

It’s difficult at the best of times to evoke the experience of a theatrical encounter in the structural, mental form of words combined into sentences… To even describe let alone evoke the raw, visceral, painful, spiritual, emotionally violent, existential experience of MAU Theatre is frankly impossible. So here goes:

The curtain on the ASB Theatre stage is down, offering no preview or indication of the dark world that lies behind it until, audience in mid-chatter, the houselights snap black and we are immersed in an excessively loud, overbearing and seemingly unending noise combining the roughest, least aesthetic kinds of both natural and industrial sounds as the curtain slowly rises.

From the beginning the abrasive, imposing sound design of Russel Walder, Marc Chesterman and director Lemi Ponifasio, drive the abstruse narrative uncompromisingly through the ninety-minute ordeal. Raw emotion drives the evolutionary journey that begins with a man appearing to discover and quickly harness control of curious forces that sound equally like chirping crickets and scraping metal.

At the foot of an enormous and dominant square geological slab stands the crumpled, painful figure of a fallen angel, red dress and tattered wings, who at times screams with fear and regret as she staggers through the unfolding events. Periodically a team of quick stepping monk-like beings appear, echoing the ritualistic movements of the first man, each time seeming more assured as the technology of their ritual science develops.

Another featured being is the quadrupedal beast that roams about both free of the concerns of the encroaching dominant species, and in danger of becoming the next tragic victim of it.

The perception of this seemingly abstract world is shifted with the introduction of known faces – first the giant visage of political asylum-seeker Ahmed Zaoui’s face projected big-brother style on the back wall, then the live appearance of Tuhoe activist Tame Iti. Dressed in a modern suit, Iti delivers a powerful mihi to us in Mâori, almost the only spoken language in the entire production and I regret not being able to understand it clearly.

So, the subjects I glean are being addressed here are about history, religion, colonisation… Whether or not the impressions I draw and the meanings I infer are close or far from those intended, I cannot deny that Tempest: Without a Body has a confronting effect. It seems to express all the turmoil and suffering that has brought life to where it is now.

The unified deliberation of the company is obvious; this isn’t just arty farty whatever, these people know what they are doing and connect through the unique working style of the MAU collective.

Long-time pacific dance lighting collaborator Helen Todd throws striking, often sparing illumination upon the events of the play, creating the sense that we’re extrapolating these images from the pervading darkness that accompanies us everywhere, just beyond the limits of our perceptions. The overall visual design is deeply impressive, supporting and increasing the stark oppression and alienation inherent with sentient existence.

Although Sala Lemi Ponifasio, the founder of the revolutionary MAU, a cultural philosophy and art collective, conceived, designed, choreographed, scripted and directed this work, it still bears the powerful sense of being a wholly collective process in bringing it to the stage. The style and tone are heavily influenced by post-apocalyptic Japanese Butoh theatre, in which Ponifasio is formatively trained. As there is no mention of Butoh in the historical notes, it is apparent MAU is to be regarded in its own right, and rightfully so.

So thanks for reading, but if you really want to get any kind of handle of your own on MAU, you have to experience it first hand. It’s an ordeal to watch, but the impressions are lasting and the sense of worthwhile achievement is strong.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments