Tempest

MAU Theatre, Corban Estate, Auckland

11/03/2007 - 16/03/2007

Production Details

CREATED and DIRECTED BY Lemi Ponifasio

Sound and visuals by Greg Wood

Lighting design by Helen Todd

PRESENTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH MAU

Tempest is a new work from Lemi Ponifasio that inflects towards the Shakespeare work, though draws away from being either a staging or an adaptation of it. Rather, Tempest is the collision of the island geography of the play and the political writings of the contemporary philosopher Giorgio Agamben, concerned with our contemporary crisis of the destitution of rights, whereby any citizen may be constituted as a detainee and any urban condition may become that of the camp.

Tempest is the performance of a staged meeting, within conditions of detention and loss of sovereign rights. The language of Tempest is Māori and its oratory signals the rebirth of an indigenous voice in the telling of the shifting conditions of political right, from the scientific journey to witness the transit of Venus that coincided with colonial conquest, to the current geopolitics of the Pacific.

Tempest is a semi-staged production preceding its world premiere in Europe 2007.

WITH

Wairere Tamaiti (Tuhoe)

Theatre ,

1 hr 30 mins, no interval

A storm to feel at home in

Review by Alexa Wilson 18th Mar 2007

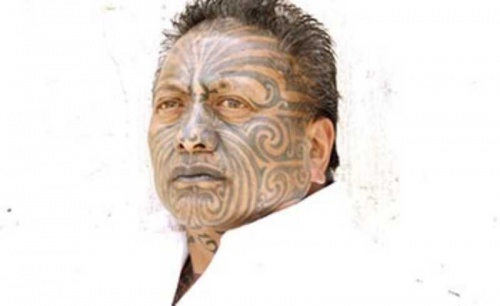

Director Lemi Ponifasio’s latest vision for his company Mau, though – as always – powerful and evocative, required a fair amount of cultural literacy based upon the themes and events of Shakespeare’s The Tempest as well as Mâori language. Mâori was spoken thoroughly throughout this Tempest by its main protagonist, renowned Mâori activist Wairere Tamaiti of the Tuhoe tribe.

Regardless of whether the audience knew either of these two things at all or well, the work was interestingly less ephemeral than usual for Mau, presenting themes more directly. This was aided within its confrontational deconstruction by personal stories of racial subjugation, oppression, colonisation, strength and resistance by Tamaiti, Ahmed Zaoui, projected filmic images and text, and traditional Mâori Haka, performed powerfully as a group, which was for me as an audience member actually more of an honour to witness and experience than anything else. All pointed towards a sense of redemption and contributed to representations of the storms inherent in our cultural history, with reference to the play Tempest.

Presuming Tempest was about (in)justice and notions of ownership and sovereignty dishonoured, then Mau’s reference was deconstructive and post-modern, challenging notions of universality especially in relation to justice, which is oppressive to indigenous peoples, and replacing that with personal stories of this oppression and resistance to it. These emphasise locality and specificity, using a voice which claims to speak for no other than themselves. The Tempest, also set on an island, is about exile of its main protagonist Prospero, who uses his magical powers to terrorise and control all those who come to the island who have wronged him (his brother betrayed him). It poses questions of ‘who owns this island?’ and, through a complicated and fascinating story, he eventually forgives everyone, for which they restore his power back in Milan.

This is an interesting platform for the interweaving of the stories of injustice of exiled and imprisoned Ahmed Zaoui in NZ, notions of imprisonment, war and colonisation of Mâori on their own land, and the breeched sovereignty issues imbued in the dishonouring of The Treaty of Waitangi by the English/Pakeha. Whether it was as strict a reference as characters being embodied was nicely blurry, though I presume Tamaiti and Ahmed Zaoui were Prospero, and Mau’s work always utilises the magic and powers of Butoh dance fused with various pacific styles and customs, linking all the cultures together ancestrally.

Notions of forgiveness were not apparent to me, unless spoken in Mâori, though exile and redemption were communicated clearly regardless of any referential subtext . Perhaps Tamaiti embodied multiple characters from the original play, this is up for interpretation. The average NZ viewer would relate more to the localized content, whereas European audiences would possibly perceive the work more intellectually as a post-colonial take on themes from Tempest.

Though there were images projected of Kuia (old women) from Tuhoe, the work contained only male performers, who performed a range of feminised shuffles, flowing arms, turns and leaps whilst grounding themselves eventually in more masculine stamping, slapping of the chest, tongue gestures, forceful and dynamic movements which evoked the Mâori war dance or challenge.

A rifle was also fired by an amazing performer, who embodied the powerful warrior beautifully, which created a shock response in the audience. A pertinent symbol of internal and external destruction of the Mâori race by the colonising English, who promptly sold different tribes guns which with they shot each other first, before the English even got to.

Because the English never fully won the New Zealand Wars, the way they colonised more fully was through land confiscation, causing ‘urban drift’ and forbidding Mâori language from being spoken in schools. These two issues were a large part of Tamiti’s story, performance and monologues, largely spoken in Mâori (I picked up words) which referenced his Whakapapa, original tribal canoes which came from Hawaiiki, different tribes, places in Aotearoa and connection to ownership or guardianship of land itself (as a bone of contention in the differing versions and cultural understandings of the Treaty of Waitangi).

Tamaiti told a story in English about how he and his peers were sent to a special rural school near where he grew up where he experienced the tale end of the Native Schools Act which forbade Mâori being spoken in schools and they were made to write ‘I will not speak Mâori’ 500 times on paper if they were caught speaking it. I presume that because he spoke most of his monologues in Mâori, as a man would if he were delivering a speech on a marae, that this was emphasising the claiming back of his native language in public (outside a Mâori context specifically). This either created an identification with those Mâori speakers in the audience or a challenge to those who could not understand to learn the language, in order to understand properly. I felt this need to do so myself strongly while I listened, although much was communicated through the intense and generous expression of his eyes and traditionally tattooed face, along with the gestures of his body. Hearing his story and seeing him perform was like seeing a rare native bird, a special and unique opportunity to listen and watch closely.

The oppression of the English way was reiterated of course through the continuation of the control, monitoring and former imprisonment of NZ’s ‘political refugee’ in exile from Algeria, Ahmed Zaoui, whose story of condemnation as a terrorist fleeing from country to country lead him to long imprisonment in NZ prison’s, with our government evidently in agreement with the Algerian government. All this was presented as video and clear evidence that all of these acts of colonisation and oppression are a breech of human rights, and residual and continued injustice.

The work became a vehicle for alternative views, opinions, experiences and expression which creates resistance and claims its own voice. This is why I hope it gets developed further and presented to more New Zealanders as well as English audiences. The message of resistance, endurance, redemption, unity of voice for marginalised and oppressed peoples, as well as believing in your own philosophy in the face of having the philosophies of others enforced upon you, should be shared and spread in the unconventional ways Mau does so.

Sound and visuals by Greg wood were immaculate and succinctly contributed to the minimalist, clear, deep aesthetic and – as always – Helen Todd’s stunning lighting brought back aspects of the ephemerality and ghostliness of Mau’s work, connecting them to visceral imagery of ancestors and spirits unseen to our eyes who connect them with past, future and present invisible worlds, for strength and guidance in ever-troubled times.

Performances by the cast were precise and evocative, as isolated solo members came together at the end to chant and move forward in the honouring (of everyone in the room) dance of challenge. As I say, it was an honour, to experience that traditional challenge. I personally feel quite at home in all these kinds of storms.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments