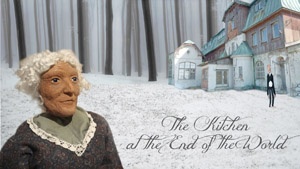

THE KITCHEN AT THE END OF THE WORLD

Greytown Little Theatre, Main Street, Greytown

18/10/2012 - 21/10/2012

Circa Two, Circa Theatre, 1 Taranaki St, Waterfront, Wellington

16/01/2015 - 24/01/2015

Production Details

The avant-garde puppet play The Kitchen at the End of the World is the inspiration for the Greytown Arts Festival’s ‘Last Piece’ theme.

It tells the story of a cynical poet and a love-sick musician who learn that there is only one remaining original combination of words and musical notes left undiscovered. The audience accompanies the marionettes on their journey to find the last song ever written.

The play was devised by the Festival director Steffen Kreft with writer William Connor. The marionette cast of characters are all handmade puppets created by Steffen, and animated by Alison Walls, Catherine Swallow and William Connor. Original music by Wellington musician and Urban Tramper, Phill Jones.

Performances – 2014:

Greytown Little Theatre, Main St. Greytown

Thurs 18 Oct, 8pm; Fri 19 Oct, 7.30pm;

Sat 20 Oct, 3.30pm; Sun 21 Oct, 6.30pm.

Saturday show sold out

Purchase Tickets

Circa Theatre, 16-25 January 2015

A powerful reminder that marionette theatre is not just a children’s art

After its sell-out debut season, Circa Theatre is proud to present the Wellington premiere of William Connor’s enchanting marionette show The Kitchen at the End of the World in January. Directed by award-winning local film maker and animator Steffen Kreft, the play is about the discovery and performance of the mythical Last Song – the world’s last truly original combination of musical notes and words.

The story takes place in a forgotten hotel on the edge of the ‘Vastness’ and is told by marionettes who know they are limited by the extent of their strings – even kissing can tangle them – but who crave what lies beyond their reach. It is a story about home and the unknown, and the courage to face everything in between.

The Kitchen at the End of the World captivated audiences at the Greytown Arts Festival in 2012, where it formed a centre-piece for the three day event, and was described as “fresh, moving”, “deep” and “intensely beautiful to watch”. For the upcoming Circa production, director Steffen Kreft has gathered the cast back together from New York and Sydney for a long-awaited second season. With a month of intensive rehearsals planned, he is aiming to lift the show to a new level: “I love the script. It works on so many levels – both playful and profound.

For me, this show is a powerful reminder that marionette theatre is not just a children’s art.”

The Kitchen at the End of the World will feature three talented actors and puppeteers: Alison Walls, Catherine Swallow and William Connor. It also features a haunting music score, written and performed live by Phill Jones. The show stars a cast of nine intricate marionettes, hand-crafted by Steffen Kreft and a stunningly detailed set drawn by Wellington artist Kelly Spencer. This will be a short season so book your tickets early.

The Kitchen at the End of the World will run from

16 – 25 January 2015 in Circa Theatre’s Circa Two (excluding Monday 19 January).

There will be a preview on 15 January.

Evening performances start at 7pm and

matinee shows on January 17, 20, 21, 23 and 24 at 11am.

On Sunday January 18 and 25, there will be just one performance a day, at 4:30pm.

Suitable for children aged 8 and upwards.

Bookings through Circa Theatre: 04 801 7992

or www.circa.co.nz

Responses from the Greytown Arts Festival season in 2012:

“Loved The Kitchen at the End of the World – Bring it to Wellington!” (Ruth Korver)

“I was enchanted with the puppet show, from start to finish….. beautiful, moving and deep” (Justine Eldred)

“Intensely beautiful to watch with a perfectly crafted provocative script that got the whole family talking” (Erica Duthie)

“I loved Kitchen at the End of the World – so well written and well acted” (Madeleine Slavick)

“Kitchen at the End of the World was a sheer delight. It was fresh, inspiring and brought tears to my eyes” (Diane McNaughton)

Lighting Design Jennifer Lal

Stage Manager Anke Szczepanski

Marionette Design Steffen Kreft

Stage Construction Terry Connor

Set Painting Kelly Spencer

Stage Hand Freya Davies

Cast

Alison Walls

Catherine Swallow

William Connor

1hr 15mins

Marionette play tugs on feelings of warmth for old values

Review by Laurie Atkinson [Reproduced with permission of Fairfax Media] 20th Jan 2015

There’s something about the guest-less hotel that features in The Kitchen at the End of the World that reminds me of The Grand Budapest Hotel. It has the same sense of isolation and a craving to preserve the past from the ravages of contemporary urban life.

At the end of the kitchen garden of the hotel is the beginning of “the Vastness,” which is seen by the characters as a place where life is busy but empty.

The marionettes who tell the story are attracted and repelled by life in the Vastness but they cannot venture there because of their strings. There’s a running joke about their problems with their strings. The young lovers, Isaac and Penelope, are wary of kissing because of getting tangled in them.

Will the hotel owner find new guests? Will the elderly cook adapt to a brave new world? Will the old man who wanders into the hotel and is rudely rejected by the robotic, fussy manager be discovered after the kindly cook feeds him and hides him away?

And then there are young Isaac, and old Orpheus and Leon who are musicians who compose the last song because all the possible original combinations of words and musical notes are about to come to an end forever.

It’s a strange, slightly disjointed story that evokes feelings of nostalgia and warmth for old values, while at the same time provoking sympathy for the one character who dares to break free by losing strings in order to venture into an uncertain future.

It’s not what you would expect of a marionette play and would most likely confuse the very young even though they would certainly be enthralled by the artistry of the puppeteers, Alison Walls, Catherine Swallow and William Connor, who pull the strings and provide the voices.

They are supported by the colourful settings, miniature props and the detailed marionette designs by Steffen Kreft, and by Phill Jones’s music and nicely timed sound effects.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Engaging at human, metaphysical and meta-theatrical levels

Review by John Smythe 17th Jan 2015

It is intriguing to contemplate what makes a puppet show work a treat when you sense that if the same story was staged as a play with full-sized actors, or made as a film shot on location, it may seem rather simplistic, prosaic even.

A tired traveller, James Thoreau, has trekked from the cluttered city to a forgotten hotel “at the edge of the Vastness”; the one that houses the titular kitchen. He encounters Penelope Goldsworth, the pregnant daughter of the hotelier; Izaac, her musician-cum-bellboy boyfriend; Mr Thinley the pernickety manager; Mr Goldsworth, the grieving hotelier and neglectful father; and the kindly Cook who has sustained them from her kitchen garden even though “no-one has booked in for 100 years” – a touch of poetic hyperbole or magic realism (given the staff have not aged that much), take your pick.

Also germane to the story are Orpheus the poet, Leon the mathematician and Andronica Burnscoop from CityMedia. Thoreau’s stasis is offset by the Penelope /Izaac love story which in turn is challenged by Isaac and his mates becoming preoccupied with composing the last possible song. You have to see it – and I heartily recommend you do – to understand how this comes to pass.

William Connor’s script, recently developed since its 2012 debut in Greytown, has Thoreau narrating the story retrospectively. He has observed and now reports what’s happened in a time past but, in the re-enactments, he doesn’t influence the action in any significant way. This, of course, is correct behaviour for a professional reporter but as a character in an unfolding drama he is rather more passive than he could be.

In literal terms, as an unofficial guest – thanks to the Cook – Thoreau does earn his keep by fixing broken windows and things, off stage. I suppose one could say the story turns out to have had a material effect on him even if not vice versa. Perhaps the idea is that, like his 19th century American namesake, he is there to invite us to philosophise on the events he observes. Even so, I can’t help but wonder if more dramatic tension would arise from the story unfolding through present action without narration, so that everyone is experiencing what happens for the first time.

The flat-walled setting, behind which the three puppeteers – William Connor, Catherine Swallow and Alison Walls – stand, depicts a fir-tree forest, the hotel lobby, the kitchen and the kitchen garden. An upper level is used as the Mr Goldsworth’s office and the hotel’s accommodation wing in the background has practical shutters which open to reveal Thoreau at one point. No designer is credited but Kelly Spencer has done a splendid job of painting it, and Stage Manager Anke Szczepanski and Stage Hand Freya Davies are very efficient at setting and striking miniature furniture and the odd prop.

Director Steffen Kreft has lovingly created the 9 marionettes, each with strongly characterised faces although the eyes are rather vacant. Nevertheless the three actors enliven them with well differentiated voices. It has to be said, though, that marionettes and the least agile and expressive puppet genre while being the most labour-intensive in their making, maintenance and operation. We therefore have to project a lot of our own humanity onto them – and we feel a special delight when the puppets’ expressions appear to change, as happens a few times here. This, I think, largely answers my initial question.

Jen Lal’s subtle lighting is enormously effective in helping to bring the characters and stories alive, and her aurora lights are a poetic treat. Phill Jones’ music, much of it performed live, supports the moods beautifully while enhancing the story’s rhythm and flow.

In essence the Vastness at the End of the World represents the great unknown beyond our present lives, to which everyone has a different response. The characters’ meta-theatrical acknowledgement that they are marionettes with strings attached that simultaneously bring them to life yet restrict them is both amusing and thought-provoking.

So the hotel houses people who may or may not decide to move on from it, or freely choose it as their preferred lifestyle. In witnessing what happens with these characters, we get to consider our own positions. That’s a good result from 75 minutes of engagement at human, metaphysical and meta-theatrical levels.

While this is an adult puppet show it should appeal to anyone from, say, 11 upwards.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Impressive yet curiously uninvolving

Review by Michael Wilson 19th Oct 2012

Actors are sometimes asked (by non-actors), “How do you remember all those words?” And they would answer they just do; it’s the least impressive part of their job, however remarkable it may seem. I have to presume the same is true of puppeteering, however impressive it may be that they don’t get their strings all tied up.

And (as a non-puppeteer) I am impressed with the intricate skills of Alison Walls, William Connor and Catherine Swallow. What’s more, they have a great many lines to remember, and just the three of them play nine characters in this full-length drama.

The marionettes are expertly constructed (by the show’s director, Steffen Kreft), dressed in character-revealing detail, and capable of fine nuances of gesture and body language.

In a clever conceit of self-referencing, they never pretend to represent flesh-and-blood human beings, frequently referring to themselves as marionettes, with a nice running gag about their strings becoming brittle with age, looking slender etc.

But The Kitchen At The End Of The World is an allegory, and the story is intended to throw light on the human condition and the issues and concerns of our world. In this context I suppose the strings might represent the thread of Life, but I wouldn’t want to tie it down.

They are also, quite clearly, an alienation device – a way of reminding the audience of the artifice of the work and that we are sitting in a theatre watching a very adroit (and plainly visible) trio of puppeteers manipulate some marionettes across a stage. And this works perfectly well.

I enjoy watching the mechanics of the performance. I even like the scene changes – slide in a length of fibreboard, flip over a scenery flat, repo the puppeteers, and in a few short seconds a whole new level is created to represent the upper floor of a hotel. Meanwhile, the constantly busy musician/sound-effects creator performs a haunting theme to further ease the transition.

I particularly enjoy the work of Phill Jones in providing a continual bed of sonic support for this production. His mix of live guitar and pre-recorded loops has an impressionistic quality, with an almost cavernous reverb at times. His sound effects are subtly underplayed – a falling pot-lid, a crackling kitchen stove, the squeaking of a glass being polished.

Director Steffen Kreft has been at some pains, I suspect, to maintain this underplayed quality throughout, often to good effect. His scenic panels manage to be small and simple (the lighting isolating each one in turn to create distinct scenes) and yet cumulatively filmic in scope.

But when applied to the performances, it results in a curiously desultory acting style that leaves me feeling uninvolved. However impressed I may be with the dexterity of the marionette work (and I am), however charming the sets and the scenery (and they are), I could do with a bolder acting style. Too often, as an audience member, I feel that my murmurs of appreciation and gentle laughter are expressing a kind of “I get what you’re doing there” response, rather than indicating my immersion in the world of the play.

And it’s not the alienation thing. Shakespeare (who, like Brecht, was right into the Verfremdungseffekt)consistently reminded his audiences that they were in a theatre, that his story was not very credible, that there was a nasty smell coming from the pit; but he had the cheek to insist that the audience believe in what they were seeing onstage.

You have to throw everything you’ve got at it, if you want to pull this off, and I think the cast of The Kitchen At The End Of The World needs to be more vocally dynamic, cheekier, create bigger characters, and show off a bit more, to help the audience lose themselves in the story.

And it’s a pretty good story. The writer, William Connor, has spun a nicely constructed tale that deals with the nature of creativity (artistic and procreative), obsolescence, the synthesising of food, and the media appropriation of just about everything. There are some good jokes to enjoy, some genuinely affecting moments, and an effect near the end that has the makings of a real coup de théâtre.

This was Opening Night, and the performers will soon gain more mastery over their material. I hope they will also break out of their low-key, somewhat awkward acting style and give the play the dynamic performances it warrants. Just because they’re puppets, it doesn’t have to be wooden.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments