The Man That Lovelock Couldn’t Beat

Circa Two, Circa Theatre, 1 Taranaki St, Waterfront, Wellington

05/04/2008 - 03/05/2008

Production Details

Three times Jack Lovelock ran against Tommy Morehu.

Three times Jack Lovelock lost.

Then there was their fourth race.

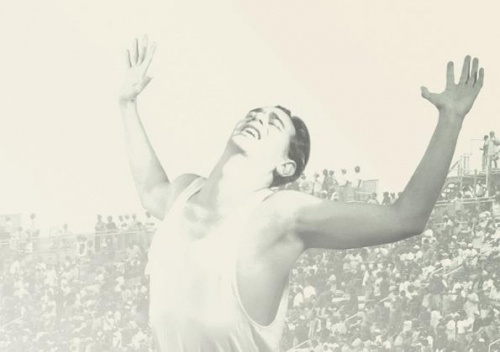

Two thousand kilometers apart they set out on the run of their lives. At the finish, one became his country’s Immortal. The other was written out of history. This is the story of the other: Tom Morehu; b. somewhere in the South Island, 1910; d. Spain, 1936.

We celebrate 2008 Olympic Year with the World Premiere of a thrilling new play that will have you urging on our Kiwi boys from the grandstand and hoping that the best man wins. Written by one of New Zealand’s most accomplished writers (The Hollow Men; Baghdad, Baby), it is brought to life by one of New Zealand’s most exciting directors (The Cape; King and Country; Niu Sila).

A New Zealand Premiere.

Performance times: Tuesday to Saturday 7.30pm, Sunday 4.30pm

Bookings on 04 801 7992 or www.circa.co.nz

RUNNING MAN

Review by Timothy O'Brien 21st Apr 2008

The politics in athletics.

Dean Parker’s new play, The Man That Lovelock Couldn’t Beat, is a highly enjoyable confection in which the techniques of the illustrated lecture are combined with the rambunctiousness of the music hall to investigate some profound questions.

Parker posits a competition between the famous runner Jack Lovelock and another Timaru boy of no historical renown, Tommy Morehu. [More]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Accessible, relevant and provocative play delivered with entertaining fluency and flair

Review by John Smythe 09th Apr 2008

This is a precessional* play: it’s true purpose radiates out (at 90 degrees) from the central plotline. By dropping the unknown Tommy Morehu into the well-known Jack Lovelock story, playwright Dean Parker sketches a class ridden heritage at odds with the egalitarian myth, traverses 72 years of political conflict and change, mounts a strong argument for politics being inextricable from sport and prods our collective conscience in the build up to the Beijing Olympics 2008.

Historical credibility is evoked through an astutely untheatrical but very human Narrator (Susan Curnow), herself a scholarship-endowed émigré to, and graduate of, Oxford University (like Lovelock), who began life in a Railway worker family (like Morehu). It is her quest to discover the elusive Tom Morehu – the titular ‘man that Lovelock couldn’t beat’ – that drives the story forward. And it’s her unresolved anger at the Lange/Douglas government, which sent her father – who’d voted Labour all his life – to an early grave, that infuses her quest with passion.

The fictional Morehu, fully realised by a mercurial Jamie McCaskill, is reflected with many facets – humour, sensitivity, cheekiness, pride, natural talent, a willing worker, an attentive lover – as he lives the experiences that develop his political awareness and conscience.

Lovelock, by contrast, is drawn two-dimensionally as politically amoral and privileged, from an authorial point of view that seems to consider it some kind of crime to be a high achiever. Nevertheless Michael Whalley manages to infuse Lovelock’s presence with a credible sense of humanity.

On the three occasions they meet and race Morehu wins but, obliged by his adoptive parents to leave school and earn his keep at 13, he is denied the support systems Lovelock enjoys as he progresses from Timaru Boys College to Otago University and Oxford (as a Rhodes Scholar). And because Morehu manages to survive the Depression by making a quid from his running, his ‘professional’ status disqualifies him from the official record of amateur sports.

Thus, in tracking their respective journeys – Lovelock’s towards the 1936 Berlin Olympics, where Hitler’s agenda was to prove the superiority of the ‘Aryan Race’; Morehu’s towards the alternative People’s Olympics that became sidelined by the Spanish Civil War – Parker pushes the view that official athletic success is a product of privilege and manipulation of the system while the disenfranchised proletariat take on the important fights, like that against Fascism in Spain.

He conveniently ignores Jesse Owens’ triumphant rebuttal to Hitler in Berlin, Oxford’s history of nurturing communist spies and the fact that the Spanish Civil War attracted soldiers of conscience from all walks of life around the globe (including from Oxford). But perhaps the play’s ‘mockumentary’ status permits it to manipulate historical detail to its greater purpose.

The important thing is that, in this Olympics and election year, The Man That Lovelock Couldn’t Beat addresses the abiding issues of race (pun probably intended) and class struggle, of equal rights and opportunity on truly level playing fields, as it runs us through a brief history of the major political ideologies that have challenged the ideals of democracy over the past 70+ years: Communism, Fascism, Nationalism, Monetarism and Globalism.

Not that it’s over-the-top agit-prop. Eschewing the myth of Brechtian ‘alienation’ – and abetted by an intelligent cast directed by Conrad Newport, all clearly aligned to the play’s greater purpose – Parker allows us to empathise emotionally with Morehu and, come the epilogue, with the Narrator, who identifies with both Tom Morehu and Jack Lovelock. It is our intellectual and emotional engagement with the ‘what if’ of Morehu’s story that allows us to consider our own positions in the current socio-political climate.

As for the coda that marks the play’s final exclamation point: those who invest whole-heartedly in the fiction should love it; those who focus more on its ‘real world’ implications may find it puzzling and unnecessary.

Bruce Phillips revels in a range of broadly-drawn characters: Irish teacher Brother Terence whose "lap the field" penance, imposed on young Tom, reveals the boy’s athletic potential; Lovelock’s more upper-crust headmaster; Bluey the dodgy Aussie bookie who works with Tom to fully exploit their corner of The Market; Wee Jimmy Cathcart, the irascible Scottish Communist activist; a commander in the Spanish Civil War.

Dena Kennedy likewise enriches proceedings with her quintet of characters: a Timaru Girl who flirts with Tommy; a no-nonsense Waitress; a Dunedin Girl; teacher Peggy Cathcart, daughter of Jimmy, whose commitment to the Struggle raises Tom’s consciousness; Jane Cathcart, Peggy’s grand-daughter, whose treasured memento feeds the upbeat ending.

The set is simply three fabric hangings on which Andrew Brettell’s excellent projections screen. Jennifer Lal’s lighting, Stephen Gallagher’s sound, Gillie Coxill’s costumes and Conrad Newport’s music all do their bit to focus and enhance this richly layered play and production. That we come out of Circa Two thinking we’ve been to school, travelled, gone to Hyde Park Corner, observed the detail of running races and witnessed first-hand the theatres of the Olympics and war, is a testament to all involved.

Only in the process of writing this review have I come to fully appreciate how much is packed into 85 minutes with such entertaining fluency and flair. As with Baghdad Baby! (2005) and The Hollow Men (2007), Dean Parker and a top team of committed professionals deliver the sort of accessible, relevant and provocative homegrown theatre that should be the rule, rather than the exception, in our recurrently funded theatres. Bravo!

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

*Precession is a word invented in the 1950s by Buckminster Fuller to explain the common phenomenon best exemplified by dropping a pebble into a pond: it travels vertically while the result radiates horizontally.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Gold medal performance

Review by Lynn Freeman 09th Apr 2008

Jack Lovelock really did have it all.

The man was an academic genius and an athletic legend. Scholarships helped his career into medicine and raw talent honed by strategy and determination led to his historic Olympic gold medal-winning run in front of Hitler.

The man in the title of Dean Parker’s play is Tommy Morehu, a kid from the same town as Lovelock but very much from the other side of the tracks. The two meet as youngsters in a school race. Morehu wins, but is disqualified. It’s the first of their three races over more than a decade.

Their paths again diverge, with Morehu working on the railways, finding love with a Communist Party Scot in England, and racing for money. Lovelock’s fortunes flourish in medicine and on the track. Morehu is Lovelock’s nemesis, but that relationship could be turned to the strategic Lovelock’s advantage.

The play is narrated engagingly by Susan Curnow, as a kind of power point presentation, with terrific images created by Andrew Brettell. Narration is a tricky business, and at times the actors are left floundering a little onstage while the exposition rolls on. It’s an episodic work, which is frustrating at times, as Newport has his actors dart on and offstage, completing rapid-fire costume and character changes.

But full credit to all involved for handling the technical challenges while putting in very watchable performances. Jamie McCaskill is charming as Morehu and Michael Whalley’s wig-impaired Lovelock has real grit on the starting line.

Bruce Phillips and Dena Kennedy confidently play 10 roles between them, with almost as many different accents.

Parker’s script is scathing of Lovelock – the narrator’s first words are of not liking the man very much and that comes through in the text and in the onstage portrayal of the man. He seems to argue that a working class man’s success on the track is somehow more pure, more worthy, than a relatively wealthy man’s success. But is that fair? Should that winning mix of talent and determination only be the lot of those who struggle to make a living?

The hugely dramatic finish is worth the wait, though we could do without the epilogue.

_______________________________

For more production details, click on the title at the top of this review. Go to Home page to see other Reviews, recent Comments and Forum postings (under Chat Back), and News.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The reality of romance

Review by Laurie Atkinson [Reproduced with permission of Fairfax Media] 09th Apr 2008

Remember Peter Jackson’s Forgotten Silver about the film-maker Colin McKenzie and aviator Richard Pearse? Well, Dean Parker has done much the same thing with Jack Lovelock and Tom Morehu except it’s on stage at Circa 2 in a highly entertaining, very funny and stimulating piece of documentary-styled theatre.

Dean Parker quoted William Godwin in a recent newspaper article: "Dismiss me from the falsehood and impossibility of history and deliver me over to the reality of romance." All good writers from Shakespeare to Stoppard have tinkered with historical fact for their own purposes.

We are introduced to Tom Morehu from Timaru, a working class boy whose ability to run fast was discovered by a Brother Terence, and who was later promoted by an Aussie bookie and by a hard-drinking, hard-line Scottish communist and his daughter whom Morehu marries.

On the other side of the track is the man with all the luck: Jack Lovelock, head prefect, Rhodes Scholar, all-round athlete, doctor. While he is seemingly inoculated from the political turmoil of the 20s and 30s, Morehu is tossed about by the Depression and he eventually takes steps to involve himself in the fight against fascism by attending the Barcelona People’s Olympics of 1936. He stays on to fight the fascists and ends up in a grave marked by a lone cabbage tree in Madrid for his pains.

As in David Geary’s Lovelock’s Dream Run, also a play about heroes, Lovelock gets debunked a bit in Parker’s play for the purposes of promoting the ordinary, forgotten, unnoticed bloke as the real hero in times when more vital things than running races are taking place in the world. Though the Beijing Olympics, of course, are never mentioned they are never far away.

Delivered as an illustrated and dramatized lecture by at times a rather supercilious "Narrator" (Susan Curnow, excellent) who describes herself as a rootless cosmopolitan teaching English in Spain, where she came across Morehu’s grave, the 85-minute show moves in Conrad Newport’s fine production with a splendid joie de vivre and is enhanced by Andrew Brettell’s top-notch video clips of the times.

Jamie McCaskill projects a devilish charm as Morehu while Michael Whalley is suitably prim and proper as Lovelock and Dena Kennedy doubles well as Jane, the ardent young communist whom Morehu marries, and as Peggy, a still-living descendant of Jane’s.

Bruce Phillips has a riot of a time playing five roles and providing most of the comedy: an Irish priest who is not above cheating to get Morehu to win races at school, the very correct headmaster of Timaru Boys High, a foul-mouthed Aussie bookie, a commander fighting the fascists in Spain, and Wee Jimmy Cathcart, who coached Tom politically as well as athletically ("the dialectical materialism of running") and who once remained seated because of too much vodka when Stalin entered a conference in Moscow.

The Man that Lovelock couldn’t Beat has the "reality of romance" which makes it thoroughly entertaining but there’s a sting in the tale.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Caricature aside, it is all done brilliantly

Review by David Colquhoun 06th Apr 2008

All week at the Turnbull Library people have been coming up to me asking if I knew about Tommy Morehu, vanquisher of Jack Lovelock, who hardly anyone had heard of before, and whose story was to be told in a new play in town. They knew I am about to publish a book about Lovelock and some seemed rather concerned that it might be too late for me to include these new revelations.

It all started on the Monday morning, after the director, Conrad Newport, and cast members were interviewed on Arts on Sunday. They played it straight faced as they were asked about Morehu. It was a real surprise, said Newport, to learn all the new information Dean Parker had found out – such a great story about a forgotten figure.

On Wednesday, the day after April 1, the Dominion Post gave more details. It was, writer Dean Parker said, a story "almost beyond belief". The next day the Capital Times had a full page feature, all of which seems to have been enough for some to wonder if this was indeed a remarkable new historical discovery.

Those following it all more closely, however, would have read an essay by Parker in the Sunday Times a few days earlier, about how a bit of fiction can help the playwright explain history, and that some parts of the play were made up – "Not all … just the ones that tugged at the heart, because that is what liars, scumbags and writers do."

There was, of course, no Tommy Morehu, orphan from Timaru, natural athlete, working class hero, who beat Lovelock three times, raced professionally in Scotland, broke the world mile record (unofficially, of course) at White City Stadium in 1935, and died fighting Franco’s fascist forces as part of the International Brigade. You will not find his name in any sporting records, or in the detailed histories of that little group of New Zealanders who took part in the Spanish Civil war.

But, enough pedantry, for what does that matter? Anyone in the audience will soon realise the play is mixing real events with some very tall stories. The play is concerned with bigger themes of history, sport and politics and Morehu’s rumbustious travels through the 1920s and 1930s are a great way to show them.

These were the years of the Great Depression, the spread of fascism, and a desperate struggle by many from the left to form popular fronts against it. The last scenes are at the 1936 anti-fascist Barcelona People’s Olympics – Morehu’s chance for sporting glory – and that was a real event. Thousands of athletes were preparing for it, until it was abruptly ended when Franco forces attacked, with planes and bombs supplied by Hitler and Mussolini. Those forgotten athletes, the play implies, are the real sporting heroes of their time. Berlin, South Africa, Beijing. It is not stated but the implication is that the same issues of bad politics and big sport are still with us today.

Jack Lovelock definitely did exist. We all know that. The Lovelock in this play though is not quite the Lovelock I know through my research and as part of my own book seeks to disentangle some of the myths about him, I was just a bit too thin skinned to feel quite comfortable with it.

Parker hasn’t written him completely unsympathetically, but he is there for laughs, a caricature of an upper class twit, and a symbol of all that Morehu wasn’t. Lovelock certainly was one of the lucky ones, untouched by the great depression, who thoroughly enjoyed being part of the privileged world of Oxford University. He was much more interested in his sport and medical career than the great political arguments between left and right that dominated the Oxford Union debates of the time. But he was not stupid, he did not shake Hitler’s hand at Berlin, and what brief comments he did make about fascism were critical ones.

That aside, it is all done brilliantly. It is a great rollicking mix of politics, sport, pathos and laughter and I enjoyed it very much indeed. It all takes place on a very simple set – a suggestion of a running track, a screen on which some key images are played, and a narrator’s lecturn.

Susan Curnow plays the narrator, a researcher recounting her discovery of the Morehu story and finding out a bit about herself on the way. She does that very well, introducing just the right amount of realism to offset all the other larger than life characters. Jamie McCaskill is a likeable Morehu and Michael Whalley gets lots of easy laughs as the dandyish Jack.

Broader still are the several characters played by Dena Kennedy and Bruce Phillips. Phillips is a riot as the eccentric priest who discovers Morehu can run, the Australian bookie who tries to make some money out of it, and the hard-drinking Scottish communist (and pioneering running coach) Jimmy Cathcart. Kennedy is just as good, and a particular highlight is the contrast between the idealistic Peggy Cathcart, who introduces Morehu to love and politics, and the simpering Jane, so anxious to share in the glory of her newly famous forebear.

There is a great coda at the end too, that will bring a smile to the face of anyone with an interest in sports history. But, of course, like most of what is told about Tommy’s very eventful life, it didn’t really happen.

____________

David Colquhoun is Curator of Manuscripts at the Alexander Turnbull Library. His book As if Running on Air: The Journals of Jack Lovelock will be published in July.

The commission was to review this play "from the point of view of athletics history", about which David knows quite a lot. John Smythe will review the production in a few days time.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments